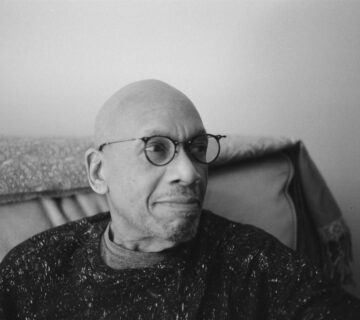

Brian Blade is perhaps best known to jazz audiences these days at the drumming dynamo that powers the Wayne Shorter Quartet. From behind the kit, he pushes against the limits of tempo, rhythm and, sometimes, reason as the group — featuring legendary saxophonist Shorter, pianist Danilo Perez and bassist John Patitucci — creates a frenetic coalescence around ideas and melodies. Shorter recruited Blade into his group in around the turn of the millennium, only a short time after Blade had formed his own group, the Fellowship Band.

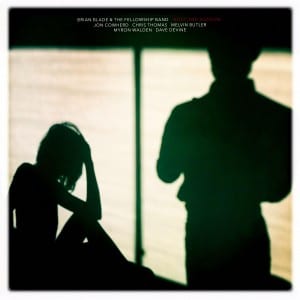

While Blade’s performances with Shorter often range from cacophonous chaos to hushed balladry, the Fellowship Band makes music that exists comfortably around the median of that spectrum. Listen to any of the tracks from Fellowship’s five albums — the group’s latest, Body and Shadow, is out today — and you’ll hear music that is deliberated and debated slowly, but with surefire spontaneity. The tunes on this new album especially are like meditations in motion; you can hear the deep breaths, the careful consideration, the absence of musical ego, as each bit of melody is birthed, develops and gives way into the next.

Blade presides over all of this from behind the kit, building the rhythmic — and sometimes even melodic and harmonic — foundations of the song with sweeping fills that provide space and structure for his fellow musicians. He oversees the Fellowship Band but never truly leads or drives the group. Along with pianist John Cowherd, Blade is one of the band’s two primary composers, and it’s certainly his ensemble, but this Baptist preacher-reared drummer sees each of the group’s five regular members as being leaders together. He calls the band “an idealistic idea — like what you want from the world. How you want a brotherhood of man to exist, somehow: That’s the challenge.” The bittersweet horn lines of Melvin Butler and Myron Walden, the strolling bass of Chris Thomas and the gospel-imbued harmonies of Cowherd’s keys all flow together with Blade’s drumming, becoming equal in the rush of inspiration and sound.

Brian Blade and the Fellowship Band is on a short tour — which will culminate with a six-night run at New York City’s Jazz Standard — celebrating Body and Shadow and 20 years of musical, personal and spiritual fellowship. The group plays Bethesda Blues & Jazz this Sunday. I spoke to Blade last week by phone to talk about the imagery and inspiration of Body and Shadow, writing music as a drummer and the relationship he sees between music, creativity and divinity.

CapitalBop: I first saw you perform with Wayne Shorter during the Kennedy Center premiere of The Unfolding. Wayne is one of the most celebrated composers in jazz and you’ve been playing with him almost as long as you’ve been with the Fellowship Band. Has he changed the way you think about composing?

Brian Blade: I think it’s his continual search, his continual not resting on what was yesterday. To write it down daily, to keep plumbing the depths of his imagination and things that inspire him. It’s just a blessing being around him, but it’s so challenging too because you realize: “Oh man! I gotta get to work.” You have to do the daily work, as he does. That’s his daily life.

CB: On that note, of his presence, it struck me that a lot of the music you make on the new album with the Fellowship Band almost feels like meditations rather than just straight jazz tunes. Was that intentional?

BB: [laughs] You know, it wasn’t so much intentional in terms of how the record became “the record,” in terms of its content. We recorded 13, 14 songs. But the one thing I’ve learned in the recording-making process with the Fellowship Band — over the years we haven’t made that many, but every time there’s this plan that I come in to record with, and then there’s what the music wants, ultimately. There’s the story that then ultimately gets told. John Cowherd bringing in that other body of work that is always so brilliant and inspiring for the band to walk into and have. So, in terms of the content on Body and Shadow, some of the songs are meditative. They just came out that way! They were the ones, to me, that ended up making the finish line. I hate to say — no, I don’t hate to say — I realize — that not everything is going to be for everyone. If there’s preconception or precondition to a listening experience, if you’re expecting bebop and blowing, well you might be disappointed! But if you want to take a trip of another kind, you might enjoy it. It kind of depends if you’re in that space to get into that journey.

CB: Body and Shadow is such an evocative title and it really hits what I think are the sonic dichotomies we’ve been talking about. What did you want that title to express? And what did you want the three title pieces [“Body and Shadow (Noon),” Body and Shadow (Morning),” and “Body and Shadow (Night)”] to express?

BB: Oh yes, thanks for asking about that. When you mention the meditative quality, or particularly “Body and Shadow,” that title came from some thoughts and ideas that Wayne has shared with us — I should say, myself, John Patitucci and Danilo Perez — over the years. It is rare that I actually write at the piano, and … I just kept playing over this thing, like over and over again. So I wanted to take the opportunity to see what the guys would render from this really simple turn of melody, or a tone poem that just kind of keeps saying the same thing. There’s kind of a “staying there” that I think I felt in myself, like: “Don’t. Let’s not go a lot of places here. Let’s just see if we can get into a certain vibration.” So that was really what I was after and I’m really glad we, hopefully, came up with three unique views of the same thing; because you can have an object but if you turn it around and look under, there’s that perspective. I think that was my desire, just to have some perspectives on one thing….

CB: I am glad you brought up the piano. In listening to the Fellowship records, and seeing how you play other instruments on the early ones, I was reminded of how Dave Grohl talks about being a drummer influencing how he writes on guitar, and how it makes him think percussively. Do you think in more percussive terms as a composer and bandleader?

BB: Yeah, I write on guitar primarily, like 99 percent of the time. And I suppose I’ve been inspired rhythmically, just walking around. A lot of times I get ideas streaming — can’t turn them off — [from] just my footsteps on the ground. These harmonic rhythmic ideas just start to course through my mind…. I do write often from that rhythmic place that wells up, simultaneously most times, with harmony and melody. Sometimes, singularly as a rhythm and a groove; a harmonic rhythm most times accompanies that, though. Then I try to get to the guitar. I never — well, very rarely — start at the drums. I do sometimes sing these things as I play certain rhythms, but it’s really at the guitar that I feel like, “Oh yeah. I can hear what the drummer — what that guy, that other guy who’s me [laughs] — might do when he plays it with the Fellowship Band.” I get a new lease on life, so to speak, when I bring in something that I’ve written and then I have to compose that part that’s mine. I’m the drummer in the band, so, “Okay, you have to play ‘this guy’s’ song,” so you have to look at it objectively to a certain degree, unlike John’s music. When he brings it in I’m already just juiced to hear it. And I know I can truly hear it for the first time and come up with something that hopefully serves that song.

CB: When you play with the Fellowship Band, at least on record, you’re not really leaning into the kind of frenetic, heavy style you use in the Wayne Shorter Quarter. With Fellowship, I hear this sense of exploration; you’re not just keeping time, you’re building this rhythmic foundation for the rest of the group. Is that similar to how you see yourself? As a bandleader from behind the kit, what do you see as your role?

BB: I guess at that point we’re all leading — or rather, being led by what the music wants in that moment. The demands of yielding to that spirit. Not my will but “thy will,” so to speak. It’s really like a surrendering…. I don’t want to control the thing. I just want to step into it and have it go higher for everyone. Even more so, I want to deliver the right thing, deliver this thing that’s going to give it power, even if that means not playing. I guess I’m always trying to be — well, I’m not trying to be, because if I’m in my head while we’re playing, I’m in trouble. It’s usually that place where I can just feel that flow where I’m not thinking, I’m just acting and reacting and hopefully feeding off everyone else’s discourse. The music tells me what to do. It’s sounds so freakin’ new age, but that’s kind of the vibe. I’m not making it, it’s making us.

CB: I do have a question about that, but you said something at the top of that answer that has me thinking. I know you were raised Baptist, so that idea of “We’re all leading together” got me thinking about Christ’s idea of “fellowship.” Was that idea at play in the original naming of the group?

BB: Yeah, it is a big part of the name of the band. The root of it [is] to bring us into that relationship with God with that inner sanctum of the secret place — because it’s so personal, it really is. I understand that, I don’t try and put my belief onto anyone else. I want to share what I feel is in my heart. But, at the same time, the Fellowship Band is an idealistic idea, like what you want from the world. How you want a brotherhood of man to exist, somehow. That’s the challenge….

CB: I don’t think that idea of the music coming in, being an outside force, is all that “new age” or out there. Whether it’s with the Fellowship Band or the Wayne Shorter Quartet, when you’re in those almost “holy roller” moments, are you playing or is the music playing you, do you feel?

BB: It’s almost like REM sleep, when you can enter the dream cycle. You’re walking around, you’re awake, but your subconscious mind is always reeling. So as soon as you sit down and fall asleep, boom! — you’re dreaming! That’s kind of like how I want to step into the music. It’s almost as if it’s always churning inside or being created or making its way through us. So, when we sit down to play, I want it to be like that light switch: “Click,” and then we’re on and we’re in it! If I can really submit myself correctly, then that is the feeling. It’s hard to describe but that’s what I want, even for the listener — for everyone involved, for everyone in the room…..

CB: So when you play these kinds of tone poems, as you said, on “Body and Shadow,” how do they translate to the live setting?

BB: Well, I don’t know! We haven’t played the songs live, so I look forward to the tour coming up so we can find out. Some songs in the past, like “Alpha and Omega” [from 2008’s Seasons of Change], we played it, since I wrote it, and always play it because it creates a new space. Same composition, same content, yet Myron and John make it so beautiful and find a new way to tell the same story every time. But there are certain songs I’ve written that we’ve never played, that we’ve recorded. So again, that has to be revealed when the time comes as well.

Join the Conversation →