When the City Paper revealed last week that Bohemian Caverns would be shutting down, the ground beneath D.C. seemed to shift.

Bohemian Caverns. Jennifer White-Torres/CapitalBop

No doubt, Bohemian is our temple to the city’s soul—a place where anyone was welcome, but the terms always belonged to the Black Arts community. It is somehow fitting that this place of worship was literally underground: Jazz parishioners don’t reach for the skies, but delve into the lore and into the soil, seeking rugged lessons.

Over the past few days, I spoke to a handful of the countless musicians who have a personal connection to Bohemian Caverns. Their various perspectives paint a moving portrait of the club’s importance. But something else in particular stands out, something very rare for conversations with musicians about clubs: Each person I spoke to almost immediately mentioned the club’s proprietor, Omrao Brown.Jazz believer, hip-hop head and devoted steward to musicians of varied stripes, Brown moved to D.C. from Boston 10 years ago to take over the club. He won the trust and even the love of the musicians of all ages who worked at his club, all while operating a three-level establishment that has included the hip-hop and dance club Liv upstairs, the restaurant Tap & Parlour on the ground floor, and the historic cave downstairs.

This weekend will be the last for Bohemian Caverns, at least in its current iteration. Bassist Kris Funn will play Friday night, and Leonard Brown—Omrao’s father, a saxophonist and ethnomusicologist—will play the final show on Saturday evening. CapitalBop staff photographer Paul Bothwell was on hand last weekend to capture a set by eminent D.C. bassist Tarus Mateen. Those photos are below, along with musicians’ reflections.

Lafayette Gilchrist, left, and Tarus Mateen. Paul Bothwell/CapitalBop

AKUA ALLRICH

vocalist, composer

I think home is the best way to describe it. That encompasses everything the caves has been for me. It’s home. It literally nurtured me, and Omrao has been like a brother to me. He’s been my champion when it comes to my career. Anything I would suggest or hint at, he would run with it. He would say, “Yeah, okay, let’s do it,” and he’d provide the space and opportunities for me to do it.

He’s just been such a huge support—and really selfless, and really inspired, in what he has created and nurtured at the cave. He and his brother and his other partner, they’re such visionaries with the cave and Liv and Tap & Parlour. It’s been such a home for me, on so many levels. I’m just so grateful for them.

Anybody who walked in there was inculcated in this vibe of just expression and connection. It’s like that environment created just the need to connect with others, on a spiritual level. And every time I stepped on that stage, I was outside of myself. It was like the audience connected with that and we were all in spirit with each other. We just wanted to connect with each other. And I swear, every time I performed at the cave it was a different audience. It was some regulars, but it was never a majority of the regulars. It was always a majority of new people, and they had to have a fantastic energy. And it would not be the same anywhere else—it is not. There are very few places where the energy is like that.

From left, Kevin Pender, Lafayette Gilchrist, Tarus Mateen and Elijah Easton perform. Paul Bothwell/CapitalBop

JASON MORAN

pianist, composer, Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz

I could be wrong, but I might say that there’s only a few places in all of America that still contain the architectural history of that early era of jazz. That alone makes it a place to deeply think about—because it’s a room that people have been going to for decades and decades, to listen to jazz.

The second thing is, when I started working in D.C., Tarus would just say, “Oh man, let’s just go over to the Caverns, ’cause you need to meet Omrao.” Any time I think I’m going to meet a jazz club owner, I’m not really expecting I’m going to be looking basically in the mirror. So here’s this dude, my age, really progressive about the kinds of music he wanted in there and the feeling he wanted in the space, and I was taken by that. So that history continued to be contemporary. It was amazing that that happened in there.

Tarus Mateen. Paul Bothwell/CapitalBop

Playing there was great—but for me, beyond that, after I would finish at the Kennedy Center, I would head over there. Omrao would text me saying, such and such is over here, come over. And we would. And that felt nice because I could meet more of the scene of musicians in D.C., who I would then come to work with, also. So it was kind of a beehive of activity—and all within an aura of goodwill, no malice. A lot of times you hear all the underside of things, but none of that existed.

I knew that if Tarus, my brother, really loved playing in this place and all these other people went over there to play, then I knew Omrao was really serving the city.

What he ends up building is a real mode of trust with musicians who say, “Yo, can I have a gig there next month?” They’d keep that kind of activity happening—even with local cats, or cats who have left, the stars, like Ben Williams or Marc Cary. They could come home and play the Kennedy Center, but they really felt like Bohemian was their home.

CAROLYN MALACHI

vocalist, composer

It gets really deep for me for several reasons. Personally, Omrao was one of the first people in D.C. to give me an opportunity to play, basically. And that was like a year or two out of college, when I was really just starting to build. Imagine going from that to the moment when I found out I was nominated for a Grammy: I was at Liv. I was on the second level of Liv, getting my makeup done, and my producer called, and then the first people I ever told about that was the audience at Liv that night. I was telling them about the importance of supporting the community, this kind of art. It was an inspiring moment.

There’s that, there’s the fact that my great-grandfather used to play there when it was called Crystal Caverns. He told hours and hours of stories about playing there. My parents and my grandparents—it was a legacy spot for them to just go and hang and chill.

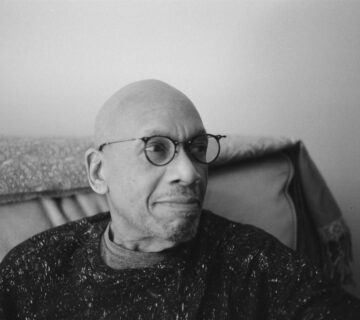

Eric Kennedy. Paul Bothwell/CapitalBop

Then lately, in the last few years, Omrao’s had me in to do New Year’s Eve a couple times. When I told my grandmother that the Caverns was closing, she was like, “What are we gonna do for New Year’s Eve now?” It’s a family tradition, which is big because we don’t even get to see each other a lot.

I grew up in D.C., and of course go-go was part of my package. And poppin’ R&B and jazz are all part of my package. But I can’t name another venue in Washington where all of those different scenes are able to mingle. It’s like the go-go heads hang out at Martini’s or Aqua or something like that. The hip-hop heads are at another spot, and the jazz heads are at another spot. It’s very rare that we get together and get to mix ideas and hear what we’re all doing. Bohemian Caverns, Liv, Tap & Parlour, that was where the community kind of gathered. Even if you didn’t go to the hip-hop show upstairs, chances are, you were standing outside for 15 minutes with the person who’s playing upstairs. Where are we gonna have that now? Where am I gonna be able to hear the Young Lions and then go upstairs and hear Sound of the City or Backyard [Band] play? Where is that gonna happen again?

Tarus Mateen. Paul Bothwell/CapitalBop

NASAR ABADEY

drummer, composer

I understand that at one time [Omrao] wanted to play saxophone, but [that didn’t work out]. It still gave him the impetus to be involved in the music on some level, and to help promote the music on a level that’s as serious and meaningful as it is.

It is said that when a child reaches the age of 7 they have developed whatever it is that they’re going to be using the rest of their life — personality and whatever else. And that what they’ve experienced by the age of 7, that becomes the rest of their life. And Omrao came up with that, with his father and his brothers and sisters. And so that’s why it was a good thing that he took possession of Bohemian Caverns—because he has that vision. And plus, he’s young enough and old enough: to have the experience and also want the experience of keeping it going. And also to know how important the older musicians were to this, and to make sure that all of us were a part of the community that he took charge of.

He wanted to keep the historical value of the club, because it was an important piece of real estate that John Coltrane and Miles Davis and all the greats of the time back in the ’60s were playing.

For all of us that liked to play there, it was not said to us what we needed to play. There was such an air of, everyone is welcome there to express themselves, in this genre which has become so expansive that it’s difficult to define it just by the word jazz. So it was that kind of an environment, one that was there for experimenting, for whatever the new voice is in the music, or the new approach—something that’s often not being exposed to a wider audience, and needs to be.

Beyond that, going back to Omrao’s vision, he saw the ability to use that real estate for two or three different generations of people. The younger people gravitated upstairs, to Liv, and then those who were a little older than that gravitated to the restaurant. And then the music was at the lower level. What I think he did with that was, he created a vision, and a place for a lot of different kinds of people. So that, to me, says more than anything—I put it on the level of John Coltrane’s great band with Elvin Jones and McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison; then you have Miles’ second great quintet with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock and Ron Carter and Tony Williams: Those musicians were together for four to five years in one band, but those four to five years were the embryo of what we’re experiencing now. They were so important in changing what we’ve experienced ever after that. Same goes with Omrao. What he has done at the caverns over the last 10 years will also go down in history as something that was a supernova. It unleashed genetic material throughout interstellar space that will last forever. ![]()

—

Interviews have been condensed.

[…] For 90 years, with a few interruptions, Bohemian Caverns served as a hub for the D.C. jazz community. When the Caverns’ closure made the newsinMarch, musicians and listeners across the country understood that they were losing more than a jazz club; they were losing a musical home, a place where they could come to find inspiration and support. […]

[…] For 90 years, with a few interruptions, Bohemian Caverns served as a hub for the D.C. jazz community. When the Caverns’ closure made the news in March, musicians and listeners across the country understood that they were losing more than a jazz club; they were losing a musical home, a place where they could come to find inspiration and support. […]

[…] to find the “real thing” in D.C.; some of the city’s most important jazz mainstays have been forced to close in recent years, and artists are having a tough time finding places to present their […]