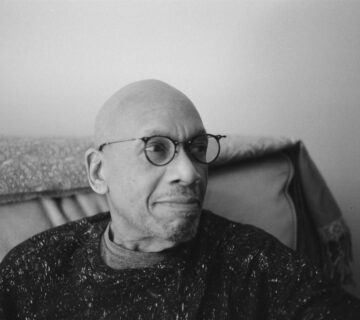

The 1990s were a time of overstated attitudes, swollen bubbles, and the warm expectation that somehow things might work out all right despite the downward tumble of the prior 20 years. How could New York City have made sense of it all without Greg Tate?

In nonstop contributions to the Village Voice, the seminal critic started with his love for music and built out a worldview, hopeful and caustic and tied to the pulse of a globalized American society. As we discuss in the interview below, Tate was an early architect of Afrofuturism; he advocated for surrealism and science fiction as artistic escape pods from a stunted discourse around race.

He’s the author of major books like Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Essays on Contemporary America and Everything But the Burden: What White People Are Taking From Black Culture, but Tate doesn’t just write. He co-founded the Black Rock Coalition in 1985, a response to tight racial pigeonholing in the music industry. And for the past 16 years, he’s played guitar, conducted and composed music for the Burnt Sugar Arkestra, a psychedelic pan-African hoedown of a band. Burnt Sugar is in D.C. tonight to play at Liv Nightclub—and judging by its last performance here in November as part of the Along Came Ra Festival, there’s no way to know what might happen.

Earlier this week, Tate spent nearly an hour discussing his adolescence in D.C., the founding of the Black Rock Coalition, the dormancy or non-dormancy of his writing career, and the continuing saga of Burnt Sugar.

CapitalBop: A few years after moving from Washington, D.C., to New York City, you became a co-founder of the Black Rock Coalition. How did that happen?

Greg Tate: Vernon [Reid] basically put out the call to a bunch of us, he just wanted to have a chat session about the resistance that was coming from Black radio, Black execs, white radio, white execs, around Black artists playing rock music. Guitar-oriented, loud rock music. He’d run into it professionally: He’d been told by other artists and producers and label cats that the going line was either, “Black people don’t want to hear that,” or “Black people can’t play that.” He wanted to have this conversation.

So we got that out of the way in the first hour and then started thinking about, what could we do to rectify the situation from a proactive standpoint? And Black Rock Coalition was born. So we began meeting just to talk about other issues … every Saturday at a gallery that a friend of ours owned down in SoHo, called Jams Gallery.

And then we put a big band situation together—Black Rock Coalition Orchestra. We had our first show at the Kitchen, in January of ’86, the Apartheid Concert. And over the next 10 years, we just continued to take our stand, and got new membership. We developed a great relationship with CBGB’s, so we started doing these this annual festival there, Stalking Heads…. And we definitely got a lot of attention from media through the years. Vernon’s managers were complaining that most of the press he got was about Black Rock, not Living Colour.

It was pretty rare—pre-conscious-hip-hop days—to find Black artists who were actually trying to be in the industry and critiqued the industry at the same time.

CB: You were involved in Afrofuturism, and were in some ways helping to define it, before that term was coined.

GT: There’s a film that came out around the same time as Mark Dery’s interview [in which he introduced the word “Afrofuturism”], with Samuel Delaney and Tricia Rose around the topic, by another friend, this filmmaker named John Akomfrah, by the name of Last Angel of History. I’m in there, Delaney’s in there, Ishmael Reed’s in there … Lee “Scratch” Perry’s in there, Sun Ra’s in there, Octavia Butler too. It’s like a beautiful compendium of the cats who were obsessed with what I call the “imagineering” of ideas—putting Black folks in a science fiction setting, in the future, or in the retro-future, listening back to ancient African kingdoms as a kind of science fiction fodder.

The thing is, even before anybody came up with the term, there was already a history. When Mark Dery came up with the term, it was already a historical subject. There was so much work already—Sun Ra had been doing his thing since the ’40s. He had begun to investigate the scholarship as far back as the ’30s, doing serious readings into mythology, cosmology, all this stuff.

CB: A constant in all that has been the will to see beyond the beyond, while also keeping things rooted to an intimate space. Things happen within certain communities. It’s continuing today, in a way that I find exciting when I look at, say, Los Angeles.

GT: Most definitely. People are constantly creating what we call “maroon spaces”—free communities, free platforms for thought and expression. I think that that’s just in the DNA of Black Atlantic culture…. There’s always the imperative towards the emancipated space, and music is of course a place where you can activate it….

All the people we consider the major avatars of Black science fiction, Black futurism, they really believed in living it as well as creating it: embodying it, or being the thing, as well as composing the thing or creating artifacts.

Sun Ra lived his future. Samuel Delaney lived his future. Octavia Butler lived her future. Very unique, free-thinking, very opinionated indviduals, who always changed the nature of the conversation. That can be at Comic-Con or WorldCom or what have you….

People are constantly creating what we call “maroon spaces”—free communities, free platforms for thought and expression. I think that that’s just in the DNA of Black Atlantic culture.

CB: Right. For instance, people I think are hungry for you to write more these days—but you’re busy doing a lot.

GT: Yeah, my Facebook page has become my default platform. You know, I’ve actually been doing a fair amount of writing over the last two years. But as writers, you kind of go where you’re invited. To be honest, too, one of the things that’s happened over the last 10 years or so is that I got invited to be a bootleg rogue scholar in academia. People pay me now to come talk about the stuff I used to write about. I’m just alive at that point of a career.

But I have a reader coming out next year on Duke University Press. So I have a lot of work that people haven’t seen, really from the ’80s on. There’s a lot of work from the last 15 years, with writing I’ve done around visual art. Museums, galleries, artist monographs, that kind of thing. A lot of interviews that people haven’t seen. With Vibe, I did a lot of interviews and profiles. Famous folks and not-so-famous folks who were making an impact on culture in the ’90s. My one interview with Miles Davis is in there, a long interview with Wayne Shorter is in there. Those were both published in a magazine that we did out of that Jams Gallery in ’85—myself and one of the other founders of Black Rock Coalition, Craig Street. You know Craig’s work as producer even if you don’t know his name: He did Meshell Ndegeocello’s Bitter, he did Cassandra Wilson’s Blue Light Till Dawn, he did Drag for KD Lang….

Craig came to New York to work at the Jams Gallery. And he and I worked on this magazine called B Culture. The first issue I did an interview with Wayne, the second issue I did one with Miles in the studio. He was making Tutu with Marcus Miller and Tommy LiPuma. He was very generous. It’s funny—if you read the interview we’re throwing these one-liners and Miles is giving us these paragraph-long answers around stuff that was pretty hilarious.

A lot of stuff is going to be in [the Tate reader]. A lot of book reviews, literary reviews. For folks who haven’t got tired of hearing me yap on the page, there’s going be like 400 pages of stuff that folks might have forgotten about.

CB: What’s drawn you to write about visual art as well as music?

GT: Ever since I was at Howard, I’ve spent a lot of time just building and hanging out with visual artists. When I was at Howard, they had such an incredible faculty in terms of Black painters who came out of the AfriCOBRAs movement.… Those were the cats who were also into the music. They were playing Coltrane and Sun Ra stuff while they were painting. I’d just go to their studios and hang out while those cats were working on their paintings.

So I always had been following what’s been going on in terms of African diasporic visual art since I was a teenager. So coming to New York, and I was working for a gallery—that gallery is the one that brought the artist David Hammons to New York and gave him his first shows there. Jams has an interesting history: They were on 57th Street, next to Stevie Wonder’s office at the time, and Stevie used to come by and ask people to tell him about the art that was on the walls. He was a big supporter.

When Jean-Michel Basquiat passed in ’88, I did this piece on Jean-Michel for the Voice. That piece, unknown to me, definitely centered me among a lot of the emerging artists or ’heads. They wanted somebody to talk about their work, so I got a lot of invitations from various artists to write about their work. It became a kind of cottage industry. I started to write about folks like Kehinde Wiley, Jeff Sonhouse, Kara Walker. And some of those folks I wrote about when I had my Vibe column.

CB: What has writing about visual art from an African diasporic perspective done for your music writing?

GT: I never thought about any of my writing as being unconnected. To me, I’m just a writer—so I never really thought of myself as rock critic first. At the Voice, when I came into it, it was the kind of place where you could come in writing about the Yankees and next week you’d be writing about post-structuralism. It was wide open, because all the editors on every section were just always looking for new voices to expand the breadth and depth of the section.

The energy that was in my early music writing, I definitely made a point of trying to translate that into writing about film, literature, political events, art. Words are our medium. And whatever you fix your gaze and your attention to, essentially you just have the alphabet to transliterate it and make it palpable and legible to the reader. To me, it was just all about trying to expand my voice, through language.

But I started out as a performance poet in D.C. in high school. There was a serious performance poetry scene going on. I was always thinking about music, reading music criticism. But the first writing I tried to do was in the vein of poetry.

CB: What was that poetry scene like in D.C. in the ’70s and ’80s, and was it connected to the music scene?

GT: It’s interesting because I think that certainly from the ’60s on, from the Black Arts Movement on, poetry and music were inextricably bound together in the politics and activism of the time—through Amiri Baraka. He was also producing concerts in Harlem, as well as writing the two seminal texts of Black music writing, Blues People and Black Music. So I come out of all of that…. I discovered that in the library.

So in my mind I was always thinking like a music journalist, music critic, because of that inspiration. But I didn’t really start writing music journalism until I got to Howard. I wrote for the Howard Hilltop. The two pieces I remember the most from that are these interviews I did with Betty Carter and Dexter Gordon…..

Then I sent Robert Christgau a little thing I wrote about a Nona Hendryx gig at the 9:30 Club back in ’81, and he started giving me assignments.… I had a friend, a good writer, Thulani Davis, who was working at the Voice. She told me to send something to the Voice, and it took me about a year to do it. I didn’t know what to send. Then I went to this Nona concert and kind of wrote this piece for myself, and sent it to him. He dug it and started giving me assignments, while I was still in D.C…. I was thinking the other day: I must have sent it through the mail. That’s the only thing I can think of, because I didn’t do faxes…. We used to do the edits on the phone. Back then you went line by line through the piece with your editor….

Over the last 10 years … I got invited to be a bootleg rogue scholar in academia. People pay me now to come talk about the stuff I used to write about.

CB: Let’s fast-forward to Burnt Sugar, the group you’ll be bringing to Bohemian Caverns. It’s been around since 1999. How did you decide to start it?

GT: Here’s the long and short of it: When I went to Coolidge High School, in the ’70s, every brother in there played some kind of instrument, was in a band, trying to be the next Jimi Hendrix or the next Larry Graham or the next Tony Williams. I gravitated toward guitar and just messed around with that, playing in a band for a hot second, trying to get my stuff together. I went to college, graduated, moved away from playing. I was more interested in studying film and journalism. I did a lot of radio in D.C.—WHUR and Pacifica—before I moved to New York. And I was doing the poetry thing. But right before I moved, I bought a guitar, a Fender Strat. Then I moved to New York and started hanging out with [James] Blood Ulmer and Vernon Reid…. I got inspired to be more serious about playing again, started playing in jam sessions. Then in the early ’90s I said, “I really wanna do this,” and threw my hat in the ring. I started this band called Women in Love. We did one album, were together about four years, but then ever since then I’ve always had a band.

Around ’99, there was a really weird, kind of associative thing that happened: I was reading MOJO magazine on two different occasions. They had this feature of, like, artists’ favorite record to play in the shower, favorite record to play on Sunday, favorite record of all time. And Ike Turner and Bootsy Collins both said their favorite record of all time was Rumours by Fleetwood Mac.

CB: Wow.

GT: Right? So I started thinking, and I said, “Well, what’s my favorite record of all time?” I didn’t really try to premeditate it—and what came up out of the subconscious was Bitches Brew. I realized immediately that it’s not because that’s my favorite Miles record, but I think the reason it’s my favorite record of all time is, it exists in a meta place. It’s like a concept record, and the way it was made is under a very mysterious, conceptual, kind of meta circumstance. When you hear about those sessions, you hear they were in the studio for just a few hours for three days. Miles liked to keep cats fresh—in and out. Everybody said they didn’t know what the hell was going on. They’d just follow Miles…. Bennie Maupin said he was apprehensive about playing with Miles, but [Miles] would say, “Just play.”

Miles said he hated the record after they recorded it. He was up in the Columbia offices months later, and something came over the secretary’s loudspeaker. He was like, “What the hell was that?” And she said, “That’s you.” [laughs] But I knew all those stories, so I think all that filtered into it…. I said, “Well man, what would it be like to try to recreate that process—that way of working—with these contemporary cats?” Cats I know from the BRC, some younger cats from New York.

Also realizing that you have this generation of improvisers who, of course, are such musical eclectics—and they’re incorporating their listening from dub music, hip-hop, downtown avant-garde, Philip Glass. All of these things are a factor as far as how they approach the guitar or the saxophone or the bass, right?

Some of the folks I called together are still with Burnt Sugar today. Jared Nickerson, who’s our anchor, on bass—musically and business-wise. Vijay Iyer was one of those people. And other cats that I’ve just known for years from the Black Rock Coalition, who were bandleaders in their own right. So we started doing these jam sessions at a studio, then a friend of ours was booking stuff … and gave us our first gig. Then things just kind of snowballed from there. I knew early on that for a band that’s working the margins, the most important thing is just to keep putting material out.

And the band changed, sometimes incrementally, sometimes dramatically, in terms of personnel, over the first five or six years. I realized it was good to get every incarnation of the band at that particular moment—go in the studio, or put out a live [record]. Having recordings out, being reviewed was our way of having a publicity team or a PR program behind us. And we got great responses from the cats at The Wire, David Fricke at Rolling Stone. He gave us a lush, lavish review for the first record.

Bitches Brew was one side of it, then there was Butch Morris. I knew him since the early ’80s. I actually met him in D.C., at a festival called New Music America. I met him and Diamanda Galas. She’s great. She did Litanies of Satan—this amazing noise vocalist, but operatically trained, and would use this crazy effect. She and Butch were friends.

He did his first formal Conduction under that title in ’85, and I was at that performance. And he went on to do a hundred Conductions before he passed. We became good friends, we talked a lot, I wrote about him and Conduction. And fast-forward to ’99, with Burnt Sugar, and I knew I didn’t want it to be a jam band. I wanted it to have that conductive element that Miles used when he was making Bitches Brew, and that Butch used to develop the whole system of doing live concerts of completely improvised conducted music. So I adapted some of Butch’s signals to our way of working, with a baton. Butch was there from the beginning, very supportive. And I’m glad we got to do a record with him and with Pete Cosey, with Melvin Gibbs and with Vijay. Butch also conducted the band several times, live, and that was always super-intense.

CB: You’ve weighed in a lot also on the mainstream in American music. There was an article by Chris Richards in the Washington Post recently questioning poptimism—basically the idea that we should all be giving extra leeway to pop music. Poptimism tends to argue that everything deserves to be considered for its effect on us, not the perceived integrity of the process that made it—but it’s become a license to sort of worship things that seem powerful.

GT: I can really narrow my personal take down to a specific [memory], which is with my band, driving back from Virginia, and one of our vocalists has a mix CD in. This tune comes on, and I’m like, “What’s that? That’s a great song.” She’s like, “That’s Miley Cyrus.” I’m like, whoa. I can’t remember the title now, but it was just a beautiful pop ballad thing.

The thing is, I’m a child of Top 40 Midwest American radio. I was born in Dayton, Ohio…. But Top 40, it was all about funk. So everything got mixed up in there. In the house, I’m listening to Motown, Sam Cooke, Nina Simone, Otis Redding, stuff my mom was playing. But when I was alone I would get hip to the 1910 Fruitgum Company and the Beatles and the Lovin’ Spoonful and it’s all just mashed up—because it’s about song.

Craig Street, that’s his whole philosophy as a producer: Fuck trends, fuck genres, fuck trying to make a hit, his thing is always making it about song. Song for him is something that’s memorable when you’re sitting down and just playing a little acoustic guitar or piano. Then you bust on that polish and it’s coming out of your speakers.

When we do a Sun Ra[-themed] show, we have all these great vocalists in the band, so we pick a lot of vocal songs—and Sun Ra had great pop hooks. He had great funk tunes, great ballads. He was a versatile 20th-century American songwriter, and could flip it any number of ways.

The thing is, I don’t think we’ve ever been in a moment in American pop culture where we weren’t influenced by gossip and perception—who people were and what they did. But as a listener I’ve always kind of jumped back and forth between the most out stuff I can find and the most sugar-coated, hookiest stuff I can find too, some of my favorite Prince tunes were some of the poppiest.…

There’s a lot of young folks that I’ve met in the past 10 to 15 years who are hip-hop centric. Anything else is like the also-ran, in a galaxy far, far away. So you definitely have folks that are comfortable inside those boxes and those boundaries. But that wasn’t the period I came up in. My period as a pop listener was the one where literally Return to Forever and Bob Marley and the Wailers played Georgetown University one year. You know what I mean? I went to a show that was Santana, Bobby Womack, the Last Poets, and Mandrill, in D.C. That was like every week at the Howard Theatre…. And the same people [who went] had all those people in their record collection. The same person that had all the Donna Summer records had all the CTI records, too. That was just what the musical culture was at that moment.

[…] descent in the Black Atlantic have been creating “maroon spaces” (Greg Tate’s term) for centuries. Indigenous people have survived their attempted extermination for more than half a […]