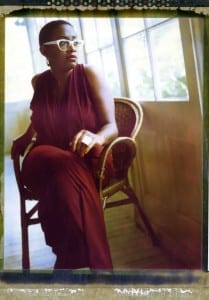

Cécile McLorin Salvant performs on Saturday at the Sixth and I Historic Synagogue, in a presentation of the Washington Performing Arts Society. Courtesy John Abbott

Go to Salvant’s concert at the Sixth and I Historic Synagogue this Saturday, and you’ll hear a voice that’s thick as a church organ, hard and fine like an etching in copper. At first you think maybe she’s setting out to annoy you: When Salvant slides from a marbled tremolo to a bulb-like vowel, the Sarah Vaughan trademark also feels like a timestamp. It’s beyond a question of influence – why should she want to come so close to being someone else? And why are all these songs she’s singing so old? Is it just me, or does her band sound like a quartet that John Lewis might have led? Why’s she making nuanced music sound so … pleasant?

But stare hard enough at prettiness, and up jumps a wart. In just three years of prominence, Salvant has proven to be the closest thing this generation of singers has to a natural master. Read the interview below, and you’ll be struck by the blend of dedicated listening, technical study, and – most of all – natural propensity that has put her on the path she’s now tracing. Yet most of the songs she sings on her latest album, WomanChild, aren’t about having it easy. Even the comic tunes will give you pause: “Nobody” was first sung by the vaudevillian Bert Williams (perhaps America’s first great comic artist, and a Black man who reinforced his complexion onstage with blackface). “You Bring out the Savage in Me” is repugnant in some very specific ways. Salvant asks what remains true about these pieces, now that so much of what produced them has been abnegated. The answer: more than we willingly know.

And consider “Jitterbug Waltz:” This prodigious young woman’s surrender before a timeless melody, and her decision to perform it in simple duo with Aaron Diehl, her pianist and main musical confidante, puts me in mind of Wayne Shorter’s line: “Jazz means I dare you.” For Salvant, accepting an inheritance can be a way of raising stakes, inviting your scrutiny.

Salvant and I spoke on the phone last month, while she was at home in Florida gearing up for an international tour. We talked about her background in Western classical music, her late initiation into the jazz world while she was in France studying political science and law, and her work with the legendary Archie Shepp – a saxophonist who makes very different music than she does, but who has taught her some gem-like lessons about the importance of simplicity, search, and focus.

CapitalBop: This jazz teacher in France, Jean-François Bonnel, heard you sing and basically insisted that you put your gift to use, right? Tell that story, and talk about what it was like to figure out that jazz wasn’t an impenetrable code.

Cécile McLorin Salvant: It was a little bit surprising and I guess I was a bit skeptical. I had listened to jazz from a very young age because my mom loved it, but it was mixed in with a lot of other music. Then when I became a teenager I started listening to my own stuff. But then moving to France and meeting this jazz musician who was a teacher at the conservatory was pretty crazy, because I was more interested in just singing classical at the conservatory, and I had been studying classical voice before that. I had been considering jazz just as a hobby, something to get my mind off things. Immediately he told me, “No, jazz should probably be your main focus, and you should probably work at this and focus most of your time on this.”

I guess he sensed a certain potential and I guess he didn’t want that to go to waste. And he saw that I was very much hesitant in really pursuing it, and I was thinking, Maybe I’ll do classical voice, or maybe law.

CB: Why do you think he felt jazz was your thing?

CMS: I think maybe some of it was just simple: He thought the tone of my voice and the sound of my voice would work well in jazz. And I had listened to a lot of Sarah Vaughan and I was basically imitating her phrasing. I was obsessed with imitating her voice. And I think he heard that I had that sort of background. Rhythm, too – I think my approach to singing and to the rhythm of singing and the song itself, in my phrasing, was maybe something that [he liked]. I’ve listened to stuff that I did back then. [laughs] It’s kind of, you know. But he has a very good ear and is very attentive and he looks for certain things. And I guess some of those things, I had.

Cécile McLorin Salvant. Courtesy John Abbott

CMS: I had sort of passively listened to all the stuff that my mom liked – which was mostly the great jazz singers. I guess later Sarah Vaughan stuff, some Nancy Wilson, later Billie Holiday. But very little instrumental jazz and even no early jazz. It is something that I listen to a lot now.

CB: What have you found most exciting about diving headlong into the jazz canon? What did you notice yourself learning?

CMS: I think just being exposed to many different kinds of jazz singing and also hearing and trying to figure out what’s going on with this instrumental music, which is such a huge part of jazz – probably in the jazz genre there might be more instrumental recordings than vocal recordings. It’s so important, so I think there was a lot of vocabulary that started to make more sense to me. It’s music you appreciate more the more you listen to it and hear how it evolved. I think I was just able to hear a lot of different kinds of singing and sort of be influenced in different ways by that kind of singing.

The biggest thing for me was to realize that it wasn’t necessary to have a pretty-sounding voice, and a lot of times having a pretty-sounding voice could actually take away from whatever you’re trying to do. I began to be fascinated by this tradition of these weird voices becoming important in jazz: Louis Armstrong had a weird voice, but he did amazing things. People like Babs Gonazlez and Blossom Dearie and Lillie Delk Christian. That changed a lot for me, because from when I was small I always strived to have a pretty voice, and then that kind of took a turn.

CB: You’ve been working with the Aaron Diehl for about a year and a half now, right? What has the passage of time allowed you two to build together?

CMS: I think what’s been most amazing with this band that I work with is that we’re slowly starting to get to a sound that’s not just kind of me sitting on top of a band. There’s something that’s happening where we have our sound and there’s a specific vibe – just from us playing together over and over and getting to know each other. I had that sort of experience before; but with the amount of gigs that we’ve had and now that we’ve had the opportunity to tour, I think it’s even more so than what I had experienced before, in France.

So that’s really amazing and it’s a privilege. And I think what’s great is, you get to learn a little about how other people deal with the problems that the music poses. And that helps because I think it’s very difficult to do this alone. And your music is enriched if you work with others consistently.

I think working with Aaron has been amazing because he’s a really dedicated musician and we’ll work on arrangements together. And I’m slowly learning how he arranges and that’s helping me be a little more precise with what I’m trying to do. His approach to improvisation and dynamics and sound and rhythm – all of those things influence me. So working with him has been really great for me.

CB: You’re writing some music. The title track of the new album, for instance. Have you always done that, or is it a new side you’re exploring?

CMS: It’s something relatively new, and it’s something I’m still trying to figure out – what it is that I do as a songwriter, and where my particular distinct voice is in that. And I think that probably takes years, and it just takes a lot more songs. I’ve been writing more and more, and hopefully I’ll write a bunch more and then start really getting into something.

CB: Do you typically write with any particular inspiration in mind?

CMS: I guess now I don’t. Any time I’m dealing with music, whether it’s practicing or performing or writing, I always have my influences floating somewhere in my head. It’s impossible to divorce yourself completely from that. But I think now I’m trying to write in a way that takes that into account but also is very personal and very authentic, and not fake. And that’s I think extremely difficult, to not be fake. I’m constantly fighting the fakeness.

CB: What is that fakeness?

CMS: When something is contrived. When something is a little too whatever, too confusing or trying to be something. You know, trying to be overly mysterious or trying to be overly political or trying to be overly feminist – any one thing that’s just trying too hard. My favorite artists and whatever I like the most have always been things that just seem natural and seem to come out of a very genuine and real place, rather than fake BS.

Sometimes you’ll lie to yourself and say, “Oh, this is cool, I just wrote this great poem.” And then you’ll read it again and realize, “I’m trying to go for this fake e.e. cummings thing,” or I’m just trying to be someone else because I like that other person. It’s a lot of editing.

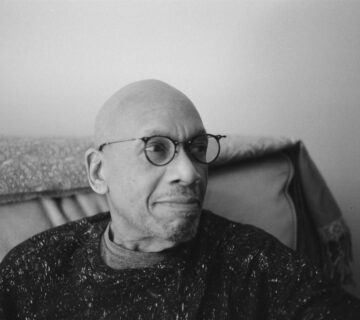

CB: You tour frequently with Archie Shepp, with his Attica Blues Band. Like you, he has always been very oriented toward the roots and outgrowths of the Black music tradition, as relates to jazz, but in a slightly different way than most. What has it been like to tour with that band, and that great figure?

CMS: I think with Attica Blues, that particular project, the music is very based in funk and blues. And I’m doing a lot of background singing, which is something I haven’t had that much experience with. So it’s really a great experience for me to work in that context. It’s not like the jazz that I usually sing. So in that sense it has been great, and just to be around Archie and talk to him and learn a little about the history of what happened at Attica.

He’s from Florida like me, but he’s from Florida at a time when the beaches were segregated. All the crazy stuff he talks about, [like] working with [John] Coltrane, and then hearing him play – it’s a lesson, always. It’s been, for me, really inspiring to work with him. And it’s given me a lot of ideas, because he has this freedom with writing that I actually find pretty rare, and he knows exactly what he wants. He’s a perfectionist and he knows exactly what he wants his music to be. There are a lot of things from that experience that have definitely changed my way of dealing with my music….

I think one of the most bizarre and kind of cool things that I did with him is that he’s very much into just obsessively repeating things. I went to his home in Massachusetts, and we were rehearsing this song, and it became sort of a trance-like state. At first it was for me to learn the song, but eventually we got into this thing where it kept going on and on and on and we kept repeating it. Things from the music end up becoming more apparent to you the more you repeat them. I don’t know how to explain it – that’s something I hadn’t really experienced with another musician. When you practice it’s one thing, but to just go on and on and on with someone else, rehearsing something, was really interesting. And that sort of approach to the music is something that’s really fascinating to me and that I think I might actually try to use.

I think any kind of repetition is obviously interesting and important when you’re practicing and you’re working at your art. That’s how you get better. But when you’re involved in that with someone else, I feel like there’s something else that happens. There’s another element. I don’t know if I even know the word or the name for it, but there’s some kind of glue that holds everything together when you’re working with someone like that. You develop this deep connection to the piece and the other person. It’s very bizarre. I haven’t had that experience with anyone else. And it’s something that stayed with me, and I sort of think back on from time to time. I think that maybe I should try that with someone else.

—

Cecile McLorin Salvant performs with her quartet at the Sixth and I Historic Synagogue at 8 p.m. on Saturday, in a presentation of the Washington Performing Arts Society. Tickets cost $25 and can be purchased here. More information is available here.

[…] Who | D.C. Musicians ← Interview | Cécile McLorin Salvant, a strong and exacting young virtuoso, finds treasure in … […]

“And consider “Jitterbug Waltz:” This prodigious young woman’s surrender before a timeless melody, and her decision to perform it in simple duo with Aaron Diehl, her pianist and main musical confidante, puts me in mind of Wayne Shorter’s line: “Jazz means I dare you.” For Salvant, accepting an inheritance can be a way of raising stakes, inviting your scrutiny.”

Cecile accompanies herself in Jitterbug Waltz, the great Aaron Diehl did not for this one. The arrangement is also her own. She seldom plays piano in public, but she did for this recording.

[…] there are two very different performances to choose from in the Maryland suburbs: On Saturday, Cécile McLorin-Salvant, the jazz tradition’s greatest young advocate and apostle, performs at the Montpelier Arts […]