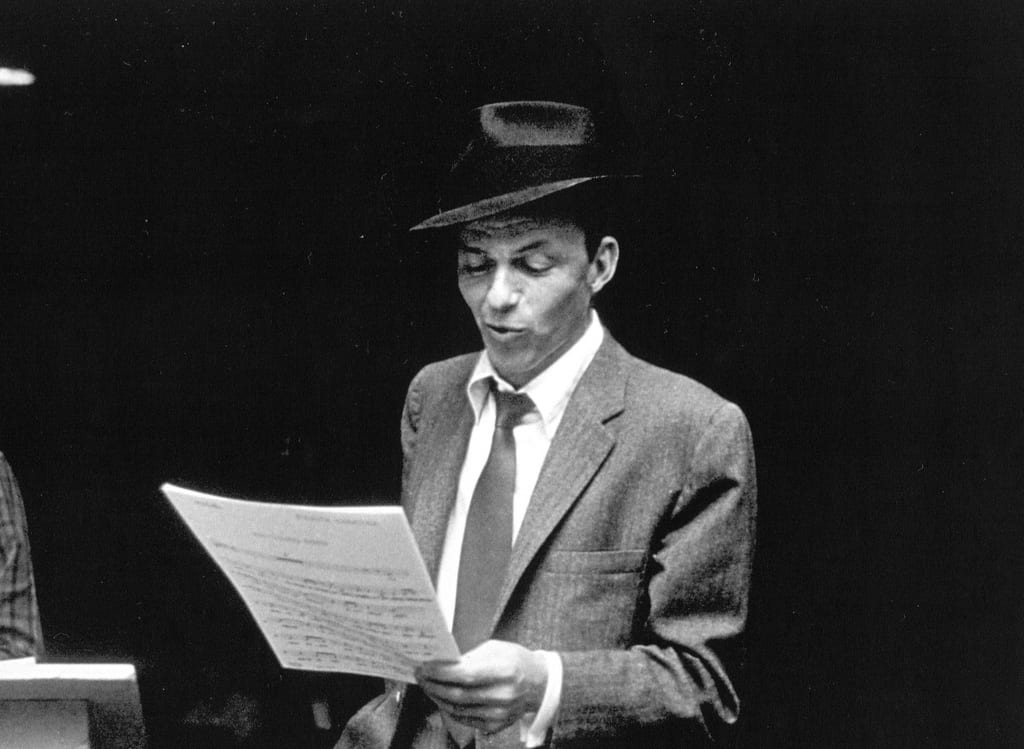

A Salute to Sinatra

Kennedy Center Millennium Stage

Sat., Dec. 12, 2015

Tribute shows are among the most demanding—and often disastrous—kinds of live music performance. Too often they are wracked by an existential peril; artists are commanded to perform in a way that’s authentic to themselves, yet they are expected to serve as a channel into the acclaimed subject’s work. So these events and albums can come off ham-handed: as either uneven, eclectic free-for-alls of style and genre, or a whitewash that casts the performers as parrots. The true artistry of the tribute lies in melding the mind and music of both artists. How can both artists become authors of a new, exciting sound and performance that bears the signatures of both?

At the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage on Dec. 12, several D.C. artists gathered to pay respect to Ol’ Blue Eyes, in celebration of his 100th birthday. The concert, titled “A Salute to Sinatra,” was presented in collaboration with D.C.-based podcast The Circus Life. All the musicians seemed to recognize the weight of the task at hand. Alex Vans, leader of power pop/rockers the Hide Away, summed up as much in his remarks before the group’s closing numbers. “How do you perform Frank Sinatra’s songs without just coming off like you’re playing songs from the great American songbook?” he said. “Getting the essence of the arrangements, while still giving off the air of Frank Sinatra, is very challenging.” Yet as with the inventive, inspiring tributes done on this stage in October celebrating Billy Strayhorn’s centennial, District musicians resiliently rose to the challenge of saluting Sinatra from a personal stance.

The key element that made the Sinatra tribute successful was that none of the performers were jazz musicians. Whether or not one agrees that Sinatra deserves a central place in the jazz canon, the songs he sung are ingrained as some of the most important exemplars of the Great American Songbook—which is itself a central part of the jazz repertoire. At Millennium Stage, without the presence of jazz haunting the proceedings, the songs made famous by Frank Sinatra were able to stand as simply that: songs he performed, and upon which his artistry was built. This allowed a much wider range of interpretation, and welcomed artists of all sorts to show how their artistry related to Frank’s.

To their best efforts, the D.C. artists who split time onstage did just that. Sultry soul outfit LATO’s lead singer Justina Johnson brought bossa nova (with sashaying rhythms courtesy of guitarist Jim Morganti, playing the nylon string guitar) and a subdued sense of romance to “The Way You Look Tonight” and “Fly Me To The Moon.” Drawing inspiration (but not repertoire) from the LP Francis Albert Sinatra & Antônio Carlos Jobim, the sparse yet sumptuous arrangement revealed all the small, savory emotional details in these songs that too often get lost in lush, string-orchestra arrangements. “Fly Me To The Moon” benefitted especially from Johnson’s transformative powers: It became less a declaration of romantic intent and more a soft spoken plea, as if heard in a back alley bistro in Rio. Much of the performance’s success lay in Johnson’s vocals, which demonstrated a warm airiness, like a Norah Jones with greater range and more substantive depth. Johnson told the audience her vision lay in wanting to draw out “the romance I believe Frank Sinatra always meant his songs to possess.”

The choices in Johnson’s performance were not entirely about herself, or about Sinatra: They were about how she related to Frank and how she interpreted what she heard in his voice. This performance set the tone for the night, and for the equally inventive performances that followed. Roots-rocking singer-songwriters Karl Straub and Stephen Dawson each took a turn on lead vocals on “I Get A Kick Out Of You” and “All Of Me.” Both brought a Blue Mountain twang and high-lonesomeness. Dawson’s country-crooned “I Get A Kick Out Of You” eliminated the ambiguity of “I” and brought the song to an intimate, personal level, while Straub’s “All of Me” bridged bluegrass with the guitar balladry done by Bing Crosby and Les Paul.

Vans and the Hide Away performed after Joe and Jenny Poppen, of Moonshine Society. Vans’ band translated Sinatra’s takes on “The Girl From Ipanema” and “It Was a Very Good Year” to Tropicalia-laced psychedelic rock, which itself was a departure from the self-stylized “power-pop rock” outfit’s typical sound. The jangle of their Stratocasters lovingly emphasized the ethereal beauty of the Jobim-penned melodies. They injected “It Was a Very Good Year” a hit of the Flamenco-Phrygian sorcery of psychedelia produced by groups like Deep Purple and Jefferson Airplane.

The Poppens’ set brought a classic city blues romp to “Stormy Weather” and “Blue Skies;” unfortunately, these tunes found the duo’s dynamics mismatched. “Stormy Weather” was the better pick for the two, as Jenny’s twang hit the buried, natural blues cadences in just the right spots. However, the electric guitar often muddled her voice, and the intermittent guitar solos left deep chasms in their wake, due to a lack of any harmony. (LATO’s performance was also plagued by guitar woes: Guitarists, you know to tune before going onstage, right?)

What all of these performances—eight songs, played by a total of four groups—managed to accomplish successfully was a balance of their own artistry with that of Frank Sinatra. And that is a crucial part of the man’s overall appeal: He has universality, and an ability to reach almost anyone, with any song. Whether singing about “Something,” sighing in the “Wee Small Hours” or whispering sweet, bossa nova nothings, Sinatra’s sound and soul worm their way into each of his songs, and into his audience’s hearts and minds.

Stephen Dawson introduced his duo’s performance with an idea that encapsulated Sinatra’s artistry. “He made the music come to him. If he did a bluegrass tune, it was no longer a bluegrass tune; it was a Sinatra tune,” Dawson told the audience. “So we’re gonna let Sinatra come to us.”

Join the Conversation →