‘Ain’t But a Few of Us:’ Willard Jenkins on why Black jazz writers’ voices matter

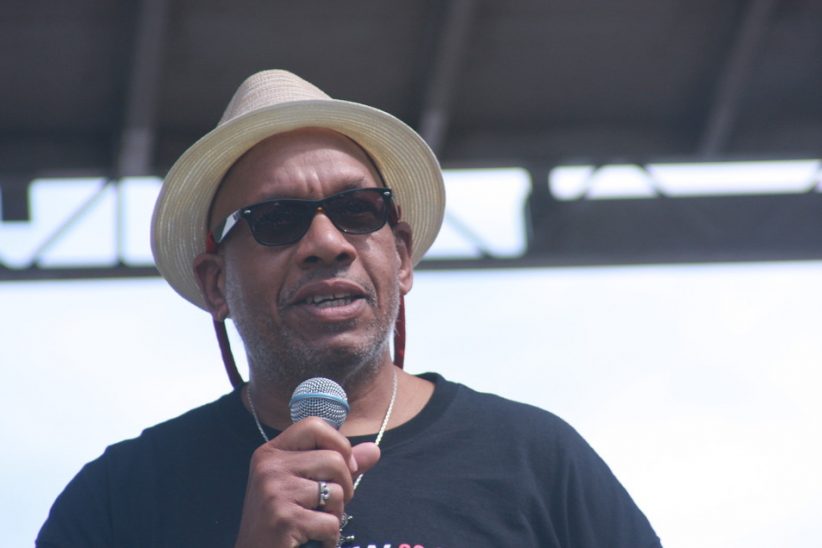

The idea for Ain’t But a Few of Us, Willard Jenkins’ new volume exploring the experiences and work of Black jazz writers, is nearly 50 years old. Known for his prolific work not only as a writer, but also as an arts administrator, advocate, organizer and educator, Jenkins came up writing for the Black Watch, the Black student newspaper of Kent State University, and other publications around Northeast Ohio. While on assignment in New York City in the 1970s, covering one of George Wein’s jazz festivals there, Jenkins decided to do something about a fundamental imbalance that he noticed around him. “There’s nobody else that looks like me among these people,” Jenkins remembers thinking. “Where are the Black writers?”

Fourteen years ago, noticing that little had changed since his 20s, Jenkins started a series on his blog, the Independent Ear, addressing this intractable problem. He began interviewing fellow Black jazz writers, starting with the great critic, poet and D.C. resident A.B. Spellman, emailing them questions and allowing them to fully expound on their journeys through the writing world. In the process, Jenkins realized that these interviews merited being collected in book form.

Many of the original conversations make up the first portion of this book, including interviews with two now-departed critical giants, Bill Brower and Greg Tate, among other testimonies that will now exist in the archive. The rest of the book collects great works of jazz criticism over the last 80 years, from seminal essays by Amiri Baraka and Stanley Crouch to modern articles by the likes of John Murph, to writings on the music by musicians like Archie Shepp and Herbie Nichols.

Jenkins, who these days serves as the artistic director of the DC Jazz Festival, is about to embark on a book tour of sorts across D.C. over the next two months. Politics and Prose hosts a roundtable discussion this Saturday, Feb. 4, at 3 p.m. There Jenkins will be joined by Don Palmer, Gene Seymour and Steve Monroe. At UDC, a JAZZforum discussion will be held on Monday, Feb. 27, at 7 p.m. at the university’s recital hall. There will be another event at Sankofa Books on Thursday, March 15. at 6 p.m.

CapitalBop spoke to Jenkins by phone this week about how this landmark work came together.

CapitalBop: Historically, the majority of jazz writing has been done done by white men. How has that affected the coverage and direction of the music?

Willard Jenkins: I don’t know that it has affected the coverage of the music in any negative way. I mean, God bless the Leonard Feathers and Dan Morgensterns and Martin Williamses of the world, who determined they would write about this music and chronicle the comings-and-goings of this music. I have no issue with those who did. But, when you think about it, when you think about where jazz came from, it came from, in great part, the African experience in America. When you think about that and think about the lack of reportage on the music or coverage of the music from that core community of the music, you realize there’s something missing. There are perspectives that are missing. I’m not going to go so far as to say – by any stretch – that the white writers, who have covered music so well down through the years, had any conspiracy on their part or anything of that nature to exclude. I’m just wanting to have the expression of those writers who come from the community of the music’s origin and their expressions on the music and their sense of the music. I think we need that as part of the overall reportage and criticism of the music.

CB: When you talk about those lacking perspectives, what do you observe those are?

WJ: Well, I’m also not sitting here listing things that have been missing down through the years on jazz writing from those who have covered the music; because, like I say, God bless those who have covered the music. What I’m saying is that you get a certain perspective from writers who, shall we say, came up in similar ways to the musicians who have sustained this music. There’s a certain understanding of how folks were raised and the communities they were raised in and the conditions that may have impacted their determination to be jazz musicians in the first place — and, some of the things that they brought from their background in the music. I think that it’s important to have the perspective of folks who have more of an understanding of those conditions, and of those elements that made and make those musicians who and what they are.

CB: Which reminds me of a quote in Jordannah Elizabeth’s interview in the book where she talks about coming up in an environment where no one had the extra money for the New York Times and had no idea what a music critic was. In your research, did you observe economic forces behind the lack of Black voices?

WJ: Like Jordannah said, there are some of us – and I count myself as fortunate, in that my father was a newspaper man, so newspapers were part of my life – [for whom] that was not part of the everyday life growing up. I think the value of that kind of influence is important, just for the foundational aspect of giving some young person or young people a sense that, “hmmm, there’s a career here perhaps,” in terms of music criticism. “There are avenues here. There is such a thing as music criticism. Maybe this is something to pursue.” So, if you don’t have those vehicles, you don’t have those outlets coming to your home on a daily basis, a weekly basis, you don’t get that kind of exposure. So, perhaps you’re missing a sense that this is one avenue of writing that might be available to you.

CB: One of the threads that emerges through all the interviews in your book is a meta-commentary on the nature of Black media, Black publications and how they seemed to have “dropped the ball” on jazz coverage.

WJ: That is an interesting thread. When you look at the categories at the beginning of the book, the categories of writers, that was something I selected in terms of grouping those writers. For example, there’s one section of freelance magazine writers: people like [John] Murph and Eugene Holly, etc., those who have written on a regular basis in the various jazz prints. Then there’s also a section called “Black Dispatch Contributors” and notably there are only two writers, Robin James and Ron Scott. That’s because – I’ll say the collective “we,” in our observation, those of us who participated in this book – the African-American publications, I’m speaking now of the weeklies, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Cleveland Call & Post, the Chicago Defender, The Amsterdam News. And then you look at the various glossy publications, like the Johnson publications, Ebony and Jet – if you go through the history of those publications, you’ll see that jazz music has never received a coverage that it deserved in terms of its historic nature in the development of Black culture in America.

It all seems to come back to economics, in the way that writers responded to that question about the Black Dispatch and the fact that the Black Dispatch has largely dropped the ball down through the years. Not that there’s necessarily a sense of jazz as artistic expression and something that it is incumbent upon us to cover, but a sense of “This is not music to make millions of dollars on,” and not a music that’s going to bring advertising revenue to these various publications. These publications have to survive and the way they survive is economically. They’ve made a determination that, perhaps, regular reportage or criticism of jazz music is not something they want to entertain, because they can’t make any money from that. … I still believe there is a moral responsibility to cover jazz from these publications.

When I did research, and looked through various prints and interviewed people who knew about the history of those publications’ coverage of jazz music, I found a lot of times, coverage of jazz music would be more in a social context: more in terms of, say, a weekly roundup column that provides the sense of “Whose performing in the community on that given week?” You might find a jazz presentation in that, but nothing substantive on writing about the latest records or anything of that nature.

CB: What conversations, and maybe even changes, do you hope this book inspires in the jazz-writing community and the Black music-writing community?

WJ: I don’t necessarily put stock in this being any kind of game changer. I just hope that, for one thing, as I always say, and I usually preface my remarks by saying: This is not a series of aggrieved writers. These are not writers who are speaking to their grievances along the way. These are writers who are talking about their journey and how they came to write about jazz music and what it has meant to them. … Now, granted, in the course of those journeys, many of them ran into obstacles and objects that, unfortunately, come back to issues of race; whether real or perceived. I just hope that people will take away from this the fact that writing about jazz is a very viable and rewarding pursuit, because you get that from most of these writers. And the example of these writers being a symbol, in one place, will positively impact future generations of writers with a potential interest for writing about this music.

Ain’t But a Few of Us is available for purchase locally at Politics & Prose, and online at dukepress.edu.