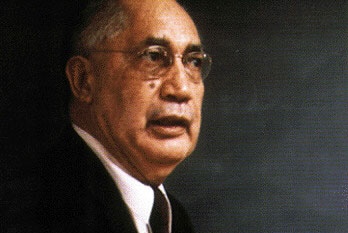

Listen to Sterling Brown

Duke Ellington said it was either good or the other kind. Sterling Brown said it was either coarse, raucous, a solidly rocking rhythm where a beating tom-tom could push out the walls and summon the police or something fit for the barnyard. When Whiteman got his hands on it, an industry turned their heads, and we have been trying to escape its enclosure ever since.

It could all be so simple.

But jazz is a four letter word and it is as simple as that.

Willie “The Lion” Smith once lectured in a Sterling Brown class at Howard University. The administration could not understand why Brown would devalue the classroom this way. Smith was a legend. But to the power structure — which thought music was the singular preserve of European classical idiom — he was a danger.

Since Brown made his transition in 1989, D.C. has been inundated with the specter of neoliberalism. In a deregulated environment, developers actually rule the city. In place of “democracy,” we have high rises that no one can afford. And now Willie “The Lion” Smith has fewer places to play. The Black tradition of musical performance and education that goes from James Reese and Mary Europe through Chuck Brown has been relegated to the margin. Capital dictates what sounds can be heard and valued. Which is why we are always hearing the sound of the police.

“The first attack is an attack on culture,” wrote Cedric Robinson. Paul Whiteman may have won. For now.

When Sterling Brown was “incarcerated” at Saint Michaels when he should have been honored, the end of an era was presaged. And though there have been concerted efforts to correct all the wrongs he experienced, there is less honesty about the world he might have imagined as the best possible future for how these Black folk and cultural traditions he loved and studied might actually survive.

[View the full ‘Jazz as Resistance’ zine]

Yes, jazz is a four letter word. It is not a style, not a genre, not a movement in and of itself. What people are trying to do when they improvise the ancestral healing sounds that come out of these instruments is to be more honest, be more sincere. Look at the eyes of Brown when he tells a lie. He is being sincere.

In the era of the New Negro, this Washingtonian knew that there were other Harlems, grittier Harlems, dusky road Harlems, way out yonder Harlems, swampy Harlems, more ramshackle Harlems, places where they actually knew how to prepare grits and had not forgotten what the sugar corn for Clara, and butter beans for Grace had meant for scores of Black people who made art that could make you weep when you heard it in Paul Robeson’s voice, which made Brown’s voice crack, because he remembered what it all sounded like the first time.

We are the ones. It could all be so simple if we understood that. If we listened to the sound that tarries in the blues of our times. If you listen to Sterling Brown.

—

FURTHER READING

Maurice Jackson and Blair Ruble, eds. DC Jazz (2019)

Maurice Jackson, Rhythms of Resistance and Resilience (2025)

Reid Badger, A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe (1995)

Sterling Brown, “Stray Notes on Jazz” in A Son’s Return (1996)

Duke Ellington, Music is My Mistress (1973)

Natalie Hopkinson, Gogo Live (2012)

DC Gentrification

Derek Hyra, Race, Class, and Politics in the Cappuccino City (2017)

Sabiyha Prince, African Americans and Gentrification in Washington, DC (2014)

Brandi Summers, Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City (2019)

Ashanté Reese, Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington, D.C. (2019)

DC Histories

Gerald Horne, Revolting Capital: Racism and Radicalism in Washington, DC, 1900-2000 (2023)

Derek Musgrove and Chris Myers Asch, Chocolate City: A History of Democracy and Race in the Nation’s Capital (2019)

Lauren Perlman, Democracy’s Capital: Black Political Power in Washington, DC, 1960s-1970s (2019)

Constance McLaughlin Green, Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital (1967)