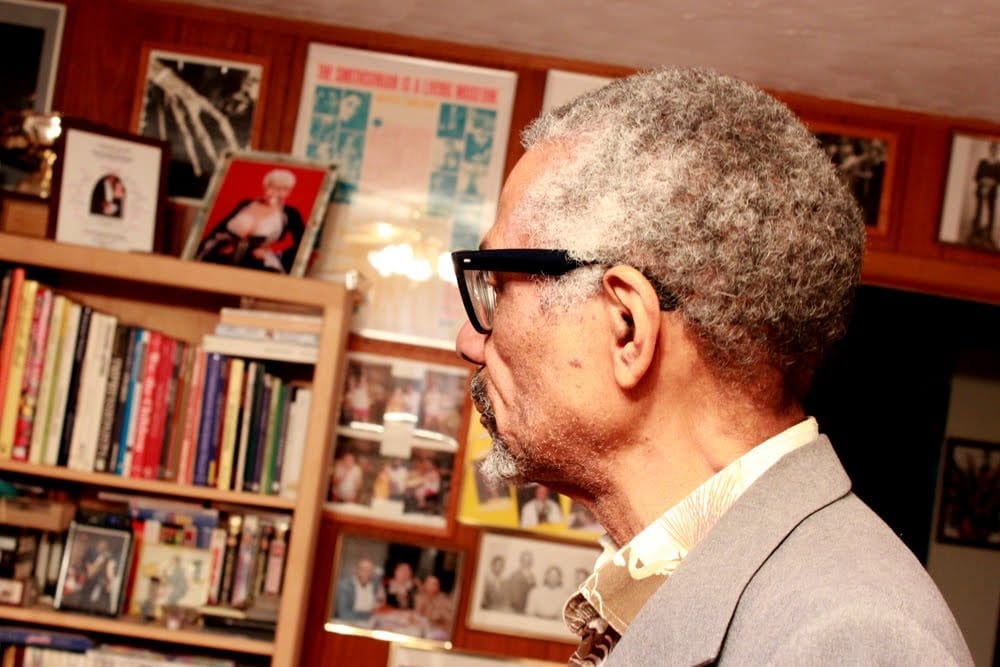

Andrew White, ‘Keeper of the Trane,’ is a living legend unknown to many

Ed. note: This article has undergone some formatting fixes for recirculation in September 2020, including the deletion of broken links to recordings of Andrew White. You can listen to a number of White’s tracks directly through CapitalBop’s SoundCloud: For more information, check out Ray Barker’s 2019 piece for CapitalBop on Andrew’s Music, White’s prolific label.

Over the course of the twentieth century, D.C. was home to many significant jazz musicians, including such luminaries as Duke Ellington, Shirley Horn, and Jelly Roll Morton. But there’s one D.C. jazz figure who is the ultimate Renaissance man: a saxophonist and multi-instrumentalist who has been performing and recording here for 50 years; a collaborator who has played with countless jazz greats and soul artists; a scholar who is known as “Keeper of the Trane” for his meticulous transcriptions of 650 John Coltrane solos (virtually every one on record); and a producer who has released thousands of products, from recordings to transcriptions to books.

One would think that with all these accomplishments, this person would be the darling of D.C.’s music community, a poster child for jazz’s greatness in the nation’s capital. But for one reason or another, this has never happened.

Andrew White began his career as the leader of an innovative quintet on one of the world’s top jazz labels, then went on to record with McCoy Tyner and Weather Report and toured with Stevie Wonder. Nowadays, the 68-year-old seems destined to fade into obscurity.

A possible reason why White hasn’t been as celebrated as certain other D.C. musicians is his refusal to compromise with the music industry. In an age when so-called DIY music production and promotion were unheard of, he founded his own label, Andrew’s Music. From there, he recorded, produced, pressed and disseminated his own records – more than 40 in all. He also used the label as a vehicle for publishing his writing, which has ranged from essays and “treatises” on music and life to adult fiction to an 850-plus-page autobiography.

With the possible exception of Sun Ra’s El Saturn label, Andrew’s Music is the longest-lasting self-run, self-produced jazz record label in the world.

White’s framed transcription of Coltrane’s “Afro-Blue” solo runs along an entire wall in his Brookland home. Giovanni Russonello/CapitalBop

On my recent visit to Washington’s other “White House,” located in the Brookland neighborhood, White let me browse the inventory of works on his imprint. “All of my records are still in print,” he mentioned, pulling out several shrink-wrapped LPs available for me to purchase. “If you’re interested, I also have copies of my autobiography for sale. Everything is in there, at least everything up till now.”

As I flipped through the impossibly thick autobiography, it quickly became apparent that this aging man had done it all, seen it all – most of which he had meticulously documented in the tome titled Everybody Loves The Sugar. Sitting down with me to discuss some important moments in his life, White pinpointed his freshman year in college as the beginning of his long career in music and the arts.

Born in D.C. but raised in Nashville, Tenn., “I came back to Washington, D.C. to attend Howard University, where my father had gone to school,” White told me. “Within six months, I was already involved on the jazz scene – and I wasn’t but 18 years old.” With an intense interest in music, he majored in music theory with a minor in Oboe. But the music program at Howard in 1960 was vastly different from how it stands today. “Back then, there were no jazz musicians there,” White recalled. “This was before the Jazz Studies program had started. There were students interested in classical music and music theory, but it was primarily an educational institution.”

[The only video of White available on YouTube shows him returning to Howard in 2007 to perform with the jazz band.]

Within the first six months of his time at Howard, White landed a gig at Bohemian Caverns with a group that came to be known as the JFK Quintet. The band featured White on alto saxophone, Ray Codrington on trumpet, Harry Kilgore on piano and Walter Booker, Jr. on bass. Drummer Billy Hart, who went on to become a major figure, was in the first incarnation. But “he had prior commitments, and so we brought in Mickey Newman,” White explained. As is the case today, Bohemian was nestled in the heart of the U Street Corridor, so many other musicians who were gigging in the area stopped by at the JFK Quintet’s Monday night gigs. Luminaries like John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy were among the many.

“Cannonball Adderley was playing around the corner at A. Bart’s International Lounge, and he’d come by on his breaks to hear us,” White recalled. “Just like we’d go and hear him on our breaks.” Adderley was enamored with the young, forward-thinking quintet, and he invited the group to New York for a recording date with Riverside Records. This led to the debut album, New Jazz Frontiers from Washington, which Adderley produced and garnered ample fanfare. But after a second Riverside LP, Young Ideas, was released, the band dissolved in September 1963.

White completed his final semester at Howard and headed for Europe to study the oboe at the Paris Conservatory of Music. It was during this time that he met his future wife, Jocelyne, and honed his chops at some of the finest jazz clubs in Paris.

“In January of 1965, I started playing heavily at the Blue Note club – that’s the club they depict in that Dexter Gordon movie [‘Round Midnight]. I was in there quite a bit, all the way up until the time I came back to the states. There were two bands each night. Kenny Clarke’s was the main band. They listed me as Andres Blanc. I started out with three weeks subbing for Ornette Coleman; something happened and he couldn’t make it over there. So they had a rhythm section there for me, including Marc Hemmeler on piano and Michel Goudry on bass.”

With the assistance of a Rockefeller grant, White returned to the United States to “perform contemporary music” as part of a two-year residency at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Upon returning to D.C., he continued performing around town, primarily with Shirley Horn’s group, which had taken up a residency at the Showboat Lounge in Adams Morgan. But White was unimpressed with his hometown’s music scene.

“The jazz scene has never been good here, in my opinion,” he said. “That’s why I’m thankful for rock ‘n’ roll; I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for rock ‘n’ roll.” This is a reference to a break he received in 1968. Stevie Wonder was scheduled to play at D.C.’s Carter Barron Amphitheatre, and at the last minute he found himself needing a bass player. White received a call from major D.C.-based bassist Keter Betts.

“I had just started playing bass around that time,” White said, “so I did the Carter Barron show and one thing led to another. I ended up staying with Stevie for almost three years.” And although it may be a stretch to think of Wonder’s music as “rock ‘n’ roll,” White uses the term for Wonder’s commercially successful R&B sound. From Wonder’s band, White landed a spot as the 5th Dimension’s bass player from 1970 until 1975. “That position and the one with Stevie helped me pay the bills,” he said with a smile.

A younger White clowns in the studio. Courtesy Andrew White

But in September 1971, White was about to embark on an adventure that would cost far more than any utility bill, and would be far more challenging than other gig he’d ever agreed to. “Around 1971, and at the age of 29, it was apparent to me that the music business, music industry, the entertainment ‘confabulation’ and/or even the art world itself, all or in part, could not and/or would not have accommodated me and/or my various artistic gifts of excess. Therefore, I took it upon myself to create an umbrella business that would shelter, nurture, develop, produce and distribute my wares in the context of my own stamina,” he explained.

Founded on the day of Coltrane’s birthday, Andrew’s Music became White’s most ambitious project. Commencing with the very first release, the self-titled solo record Andrew Nathaniel White II, the label was a vehicle for not only White but the various players who regularly performed with him. Steve Novosel, one of D.C.’s most accomplished bassists who also recorded with Rahsaan Roland Kirk, first joined forces with White in 1963 and has appeared on more than a dozen of White’s LPs. “Steve’s been with me for 48 years,” he noted, “and there’s not a finer bass player out there.”

Year after year, White released recordings that demonstrate his diversity as a musician and his interest in exploring wildly variant soundscapes. A survey of his 40-plus recordings gives insight into his interest in everything from classical oboe compositions to early-1970s funk. One consistency among all of his albums is the recording quality; even the live recordings are well balanced and mastered.

White stands next to “Saxophonitis,” one of the 40-plus albums he has released on Andrew’s Music. Giovanni Russonello/CapitalBop

As a sideman throughout the years, White played saxophone on McCoy Tyner’s LP Asante and oboe on the pianist’s album Cosmos; bass and English horn on the famous Weather Report albums I Sing the Body Electric and Sweetnighter; and saxophone on Bobby Watson’s E.T.A.

Today, White rarely performs, and has stopped composing and recording at the frightful clip he maintained for years. Ask the younger musicians coming up on the District’s jazz scene, and some simply do not know who White is.

It’s shocking that White hasn’t received more recognition for his work. He has delivered the world a complete package: the adroit multi-instrumentalist and consummate showman, the inspired composer who is an equally formidable improviser, the dedicated producer and chronicler, and the serious scholar who isn’t afraid to clown. He has been making uncompromised music through his company for the last 40 years. One thing is for sure: White’s name and label will forever be two of the most important components of D.C. jazz history.

Andrew White, Bohemian Caverns, DC, Eric Dolphy, jazz, John Coltrane, Washington