House without organs: Rhizome DC, hear and now

The word – the troubling, discouraging word – didn’t come from their landlord, remembers Layne Garrett. Sometime late in the summer of 2020, while the world was still discovering what it means to be ill-prepared for a global pandemic, someone was perusing a website that tracks development projects in D.C., and noticed a proposal for affordable housing to be built in the Takoma neighborhood. The proposal was already ploughing its way through the approval process. The address was 6950 Maple Street: the address of Rhizome DC.

The information hovered around a while, a rumor waiting to be confirmed, but after a couple of perfunctory ANC meetings and calls for public comment, the reality set in. Once again, a vital physical site of the Washington avant-garde music and arts scene would be run out of Dodge by the big guns of sovereign real estate.

Now, you can’t get all teary-eyed and heartbroken over things. Leadbelly famously told us in song that D.C. is a “bourgeois town.” And Marx warned us that “private property has already been abolished for nine-tenths of the population.” The scruffy, white, two-story house that has hosted over 700 public programs – many of them musical, some plurality of these loosely definable as jazz – invited participants to expand, grow and explore in the finest of countercultural traditions. It was, however, always as doomed as it was valuable, and nothing other than a genetic-level rewriting of the terms by which art can claim and hold space will keep it from happening again and again.

Rhizome’s very existence is a testament to the cynical game of whack-a-mole that DC developers have been playing with the underground music community for as long as I’ve been aware of the existence of such a community. Hell, isn’t dc space a Starbucks now? But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Steve Korn was part of the original six-person collective that formed in the spring of 2015 to do something that would eventually become the dense wad of disparate activities unfolding and enfolding at the house on Maple Street Northwest, very close to the D.C.-Maryland line. “I met Steve,” Layne recalled in an interview with Rhizome documentarian Tatev Sargsyan, “because we both did this synthesizer workshop in Baltimore, and he gave me a ride. I don’t think we’d ever met before then, but somebody connected us because I needed a ride.” It was Steve’s idea to name the collective and its project Rhizome, after a concept developed in the first chapter of A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze and French psychoanalyst Félix Guattari.

Poet Leslie Bumstead remembers that, in early meetings, she and the other Rhizome founders “bonded over trusting our kids, sharing our ideals and our fears, and talking about our myriad interests while our kids played together.” They became friends as unschoolers – parents who lived and learned alongside their children, liberated from the ideologies of traditional schooling and coercive parenting.

“It was a beautiful life outside of conventional models of working and living,” Leslie told me in an email. “When I think back on it, creating Rhizome together seems like a logical next step. The way Rhizome works – a combination of embracing the unknown, trusting ourselves and each other, supporting experiment and uncertainty, and seeking knowledge in a field of equal players – is exactly how unschooling works.”

The project of social revolution requires a considerable amount of unschooling: for the oppressed, out of habits of acquiescence to oppression; for the oppressor, into a realization that their privileged position atop the social hierarchy is undeserved and can only be maintained at great and self-damaging expense.

“Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.” Article 29, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948.

In addition to Leslie, Steve and Layne, Rhizome’s founders included Ann Bemon, a specialist in urban farming whose composting with earthworms workshop was an early Rhizome offering; Dennis Lucarelli, a scientist who helped add serious topical discussions to the group’s programming mix; and Tom White, who took on the bulk of the extensive rehabilitation work needed to open the house, and whom this writer remembers as always projecting the warmest greetings. Before signing a lease for the house in Takoma, the group did a few shows at Back Alley Theater, a performance space with a subversive and itinerant history dating back to its founding in 1967, in an alley in Mt. Pleasant. (Since 2011, thanks to drummer Amanda Huron, the theater has operated out of the basement of the housing co-op at 14th and Kennedy Streets NW.)

The house needed work before it could open its doors for public programs. The humble, white house had last functioned as a salon where women had their hair coiffed, and had been vacant for some time when the group took it over. Walls were in need of repair. There had been some flooding. Moldy, water-logged flooring needed to be pulled up, the electrical system brought up to code. “We were at that phase where we had ideas about how we wanted it to be,” Steve reflected in an interview, “but we really had no idea what was actually going to happen, who was going to show up, if anyone was going to show up and use the space as we had hoped.”

D.C. showed up to Rhizome in force. Steve almost wiped out his car on the snowy night that he drove down from Takoma Park to Union Arts – a warehouse on the edge of what had begun to be called the Union Market District – to meet with Luke Stewart and talk about relocating the powerful music programming he had been successfully curating there. Steve believes this would have been in late December 2015 or early January 2016. Before Union Arts, Stewart – a jazz musician and sonic experimentalist – had booked shows in a loft space called Red Door, then located in the Mount Vernon neighborhood’s Gold Leaf Studios. After Red Door closed in early 2012, Stewart migrated his loft shows to Union Arts. (Union was the home for a time of CapitalBop’s DC Jazz Loft, among other shows, and Stewart is also a co-founder of CapitalBop.)

From the beginning, “the goal was to put jazz in that context of the contemporary DIY community, almost in a way of reclaiming that space for that music which birthed DIY in D.C. and elsewhere – like the warehouse/loft sort of vibe where, I guess, the connotation at that time, and probably still today, is punk bands, a lot of sweaty dudes with tattoos and piercings in a warehouse or something, and mostly white people,” Stewart explained to Sargsyan. “When in reality, going back to many, many decades ago, it was jazz that was in those spaces, and it was specifically radical Black jazz music that was in those spaces. It was that legacy that I wanted to reclaim…. In those first shows, especially at Gold Leaf, Red Door, most of the people that came were already used to going there to see their favorite indie bands, came there to see jazz and were exposed to jazz for the first time. So, those same people that had no idea about what was going on were exposed to this music.”

Union Arts was an extraordinarily beautiful space, with good sight-lines and a great sound for both acoustic and electric music. I had so many memorable experiences there. Aaron Martin was a marvelous human and a great alto saxophonist whose death in March of 2021 left a silent void in the Washington jazz community. It was at Union that I had first started hearing Aaron a lot, enough to get a feel for his unique contributions to his instrument and to music. The last place I heard him play was the living room at Rhizome.

Of course, in that great pattern of cultural displacement in D.C., Union Arts and its music were forced out. A developer bought the building in late 2015 with the intention of erecting in its place an art-themed boutique hotel. Stewart, maybe to his credit, didn’t exit without a fight, rallying a social media campaign to bring pressure wherever pressure could be applied.

In addition to hosting a run of outstanding concerts presenting local and international musicians in an intimate setting, Union Arts had also been the site of a weekly improvised jam session. On that fateful wintery night, Steve invited Union Arts’s improv crew — which, in addition to Luke and Layne, included Pat Cain, Nate Scheible, and Phong Tran — to bring their sessions uptown, to do their weekly performance thing in the house at Rhizome and to start putting on shows there. In short order, that group, rebranded as the Maple House Collective, brought Stewart’s dynamism combined with the Union Arts network and its audience to Rhizome.

This would prove fortuitous, as a few weeks after Steve’s entreaty to the Maple House Collective, another vital D.C. institution, Bohemian Caverns, announced its own eviction of creative music. When owner Omrao Brown closed the club, which had put on a nightly calendar of national and local acts from across the jazz spectrum, it also put Transparent Productions out of a home. Rhizome immediately became an obvious home for this long-lived presenting operation, which focuses on music that lives at the margins of genre.

I was a member of the five-person collective that founded and produced Transparent’s earliest shows; the organization is currently headed by Bobby Hill and Clay Fink. We had deep ties in Takoma Park going back to the early 2000s, when some of our best shows occurred in Jennifer Carter’s Sangha Fair Trade locations. There, concert-goers could shop for incense, candles and Buddhist curios between sets. Omrao and Transparent had continued that momentum in Bohemian Caverns’ storied and faux-stalactited subterranean space. Returning to Takoma was only natural for Transparent, which soon began presenting the majority of its shows in Rhizome’s living room, or the spacious yard out back.

If that wasn’t enough, at the same time that Rhizome was revving up, Jeff Surak was looking for a new space for the experimental music scene he had been cultivating at Pyramid Atlantic two miles away on Georgia Avenue in Silver Spring, after he too experienced cultural displacement when the building sold around the same time. Pyramid Atlantic moved its printmaking studios to Hyattsville to make room for a Sherwin Williams paint store, but Surak’s experimental music also would find a new home in Takoma.

Thus, explains Steve, “within a period of less than six months, the activities that were already established with presenters and a community across Union Arts, Pyramid Atlantic, and Bohemian Caverns all kind of came over to Rhizome. You know, like, hey that’s what we want – a space for stuff that doesn’t have a place but needs to. In a way, it’s unfortunate that all these places got developed and their creative activities got displaced, but luckily we were in a place to take them in and give them a home at Rhizome.”

Becoming a catch-all underground music venue, however, was never the bullseye at the center of the core group’s intentions. “I don’t think experimental music is contrary to the vision. It’s just that it wasn’t like explicitly part of the vision, if that makes sense,” Layne explained. “We used to have this program called Unthings, which was once-a-week for homeschooled kids, like three or four hours. And we would rotate the facilitators, but I facilitated it sometimes. I had some great things happen in those sessions.”

“I brought in a bunch of recordings of different percussion music and played them,” he continued. “And we chose one to try to learn, which was this gamelan piece that seemed relatively simple. And so we tuned all these xylophones to the right scale to play this piece. And a couple of kids made these bamboo flutes and we tried to tune those.”

Leslie Bumstead also has fond memories of the educational activities for young humans supported by the house: “Unthings involved a few artists and a bunch of kids, and we had the whole house in which to make art & music, play games, write, tell stories, and improvise. We dyed wool and silk, made ink from walnuts, drew giant magical maps, and sorted seeds for a nearby urban farm,” she wrote in an email. “To have a whole house to inhabit for a group of equals of all ages, engaging in art and play and collaboration, was a dream.”

In fact, the very first public program was an educational AfroFuturist workshop held on Jan. 30, 2016, with artists Ayodamola Okunseinde and Salome Asega asking their Black participants to create designs for future technological artifacts to be included in an Iyapo Repository. “We were conscious of wanting to have a diverse space,” recalled Steve. “We wanted it to be an open and safe space. We did not want it to be a white elitist space. There’s plenty of that in D.C. We did not want to put all our work into creating another one of those.”

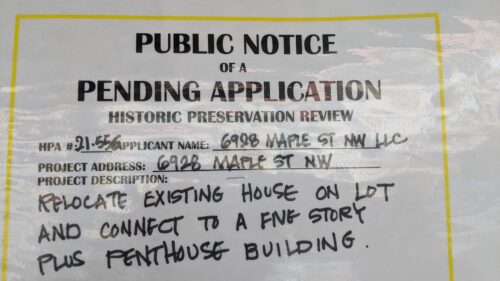

When word first hit that the developers were coming and that the time-worn house would be – not razed – but taken out of the collective’s control and physically relocated as a historical keepsake to one corner of the lot, there was a panicked sense that closure was imminent. Some energy went into a hasty scavenger hunt for an alternative space. Would it have parking and be near a Metro stop and have ample yard space for socializing, children’s play and outdoor performances? (Eyes well with tears as I remember the bird that sang along with Fay Victor from a tree branch above her head. Did you hear that? Were you there?)

Several closing dates have floated through the rumor mill, but Layne Garrett, perhaps toughened by all of this, maybe just stoic, wants you to know that all such chatter is fake news. He regularly checks a D.C. government website that posts all public records and knows that the construction crews can’t start working without a building permit, which to date has not been issued. He always wanted to be a part of a house built not of bricks and boards, but Art. He paints a picture of a giant forklift scooping up the dear little house while some amazing ensemble rocks away in the front room. The audience doesn’t notice. The band doesn’t miss a beat.

Steve maintains a larger vision for Rhizome. “It wasn’t just the name, it was actually the whole idea – to make a physical space that is a rhizome – non-hierarchical, not like a tree, where everything is set up and branches out, but organic and growing like crabgrass, wherever the conditions are fertile,” he said. “One of the key points of the manifesto is that there should be a Rhizome in every city, in every community. (I know that Yes We Cannibal is doing that in Baton Rouge.) I think that should still be a goal. How do we enable, how do we help other communities to create a similar space, a similar idea? I don’t want Rhizome to be thought of as a one-time thing. I’d like to see it be a start or a model where it could grow (like a rhizome) across the country.”

Space is the place. Looking back, Layne is proud of helping to launch and sustain so many different ideas enacted by so many different people and communities, and of creating so many opportunities for people to hear world class music in a living room.

“Rhizome has brought so much to my life,” Leslie said. “I have learned from the artists who are part of the local community, and those who have traveled briefly through. I’ve been amazed and inspired by how many people out there are imagining/creating different worlds through their art. My work as a poet has been inspired by many Rhizome experiences. This is a location of spirit and energy. It has always struck me that when new people walk into Rhizome they almost immediately marvel at the magic of the space. It’s just a little drafty house, and yet it conveys so much more. Perhaps, because it is a space of creation and comfort, exploration and acceptance. We push the boundaries of conventions that serve to mute or tame us, we make connections we could never have expected, and find ways to support each other against the forces of this hyper-capitalist landscape that does not want our art or community or exploration.”

Just a little drafty house, but God bless the child that’s got his own.

Author’s note: My tremendous gratitude goes out to Rhizome documentarian Tatev Sargsyan, without whose archives writing this article would have been impossible.

avant-garde, DC, DC jazz, jazz, jazz loft, Rhizome DC, Washington