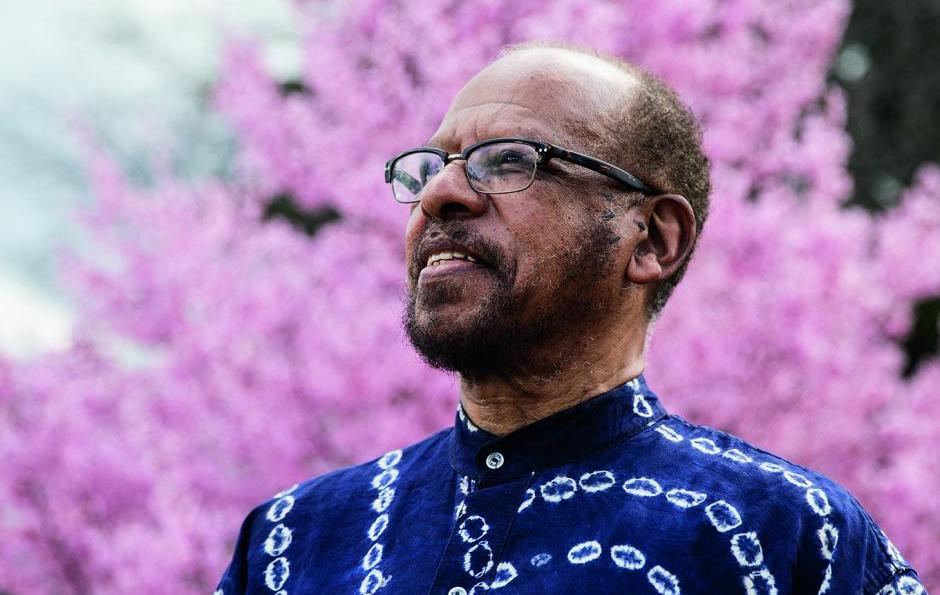

‘He was very powerful, but he was not loud:’ D.C.’s jazz community remembers Brother Ah

Brother Ah spent his life dedicated to music. He was a multi-instrumentalist, an educator, a radio DJ, a philosopher. And as his colleagues in the D.C. community attest, it was that flexibility — that willingness to serve the music in any way that was needed — that left an impression on all of them.

Brother Ah, who died on May 31, is best remembered internationally for his work as a performer, particularly as a French horn player in groups ranging from the Sun Ra Arkestra to the Gil Evans Orchestra, and for his own projects as a bandleader, which often emanated from the jazz community but reached toward unclassifiable sorts of improvisation.

But in D.C., where he moved in middle-age along with his wife Ayana, he was also known for his radio program on WPFW 89.3 FM, “The Jazz Collectors,” which became a pillar of D.C.’s airwaves during its decades-long run.

“Yeah, great artists had him,” DJ and music curator Bobby Hill wrote to CapitalBop, reflecting on the life of his longtime friend. “But we got him too!”

Dr. Thomas Stanley, a multidisciplinary artist and philosopher, was one of Brother Ah’s many students at Brown University, and later among his colleagues at WPFW. Stanley likened Brother Ah’s approach to listening — which he had termed “sound awareness” — to similar philosophies popularized by Pauline Oliveros and John Cage. In this approach, “every sound is like a lozenge that you have to dissolve in your mouth,” Stanley told CapitalBop. “He alerted us to listening as a practice that’s about health, both individually and socially.”

Brother Ah, who was born Robert Northern, lived this philosophy, both as a musician and as a DJ. His immersive radio programs were thoroughly planned but never predictable. “His playlist had depth and range,” recalled Tony Leon, who worked with Brother Ah for years as his personal radio engineer. “From Farrakhan’s violin to Stravinsky, from Prince to the Duke [Ellington], from Tito [Puente] to Mahalia [Jackson], and from the sound of a Zebra to the dialect of the African American.”

This patient, subtle approach to listening was matched by Brother Ah’s gentle, kind demeanor. “He was very powerful, but he was not loud,” Stanley recalled.

Celebrated D.C. drummer Nasar Abadey put it even more simply: “[Brother Ah] was a gentle soul.” The two were longtime bandmates in multiple ensembles. Brother Ah, Abadey recalled, would hear a cricket during band practice and stop the piece to get the insect outside safely.

Abadey also spoke reverently of Brother Ah’s philosophy. “He taught me we can have an impact on the environment,” he told CapitalBop. “Sound creates form.”

Robert Northern was born in Kinston, N.C., on May 21, 1934. Shortly after Northern’s birth, his parents — who lived in New York City by then, but had been visiting family — were forced to leave town and head back north after tensions escalated between his father and the Ku Klux Klan. After living for some time in Harlem, where his father worked as an entertainer at The Cotton Club, the family eventually settled in the South Bronx.

From a young age, Northern was drawn to musical expression. Starting on bugle, he transitioned to the French horn in his teens while studying at The High School of Performing Arts in Midtown Manhattan. He demonstrated a striking aptitude for the difficult instrument within a year of picking it up, and following a particularly rousing performance of Dvorak’s “New World” Symphony, he was offered a full scholarship to the Manhattan School of Music.

While there, Northern studied classical French horn under musician and composer Gunther Schuller. But along with several other fledgling musicians who would become jazz greats, such as Max Roach, Julius Watkins, John Lewis, Joe Wilder, and Donald Byrd, Northern was barred from studying jazz — or any Black music — and was instead pushed to study the European classical canon.

The Korean War forced an early end to Northern’s time at MSM, and he would spend four years, from 1953-57, in the Air Force. Although he hoped to return to New York and continue his studies, his scholarship was no longer honored.

With encouragement from Schuller, in 1957 Northern packed up his horn and relocated to Europe to study and work in Vienna. While there, Northern worked as a hornist in both the Vienna Philharmonic and the Wiesbaden Symphony — classical orchestras whose American counterparts still barred Black musicians from membership.

The next year, after his father had a stroke, Northern returned to the United States, where he would go on to break several such racial barriers, becoming the first Black musician in both New York’s Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra.

Around that time, Northern also began seeking work on New York’s booming jazz scene. As he recounted to fellow WPFW radio personalities Rusty Hassan and Willard Jenkins in a 2018 interview for Open Sky Jazz, “My real goal in life was to be a jazz trumpet player, not a symphonic horn player, even though I was getting more work as a symphony player.”

In 1959, Northern exploded onto the New York recording scene. His first appearance was on Gil Evans’s record Great Jazz Standards, in which he was featured particularly on the John Lewis ballad “Django.” Over the next decade, Northern participated as a vital contributor to seminal moments in American musical history, working with Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Oliver Nelson and Quincy Jones, among many others.

By 1963, Northern began to more thoroughly explore his interest in spiritual and creative music. This began with his first experience hearing Sun Ra perform at the storied New York jazz club Slugs’ Saloon; it would result in a 10-year membership in Ra’s Arkestra. With that group, Northern began soloing and developing an approach to music that would shape his later career as a bandleader.

Meanwhile, Northern began work as an educator. Initially teaching brass at an elementary school in the South Bronx, by 1971 Northern had begun teaching at Dartmouth College, where he took over a position vacated byDon Cherry. After three and a half years there, Northern joined the faculty at Brown University, where he would stay for nine years. It was at Dartmouth that Northern adopted the name “Brother Ah.” Initially it was in jest, as students would call Northern “brother ahhhhh” in reference to a calming verbal tick he had. However, after deepening his spiritual understanding with the phonetic sound “ahh,” particularly its connection with Aah, the ancient Egyptian moon deity, Northern willingly took the name Brother Ah as his own.

Under that name, he transitioned from session work and into a focus on leading his own ensembles. He released his first album, Sound Awareness, in 1973. It featured Roach, his old friend, reading poetry on Side B. That record earned immediate and lasting acclaim. The writer Ron Welburn called Brother Ah’s work an “important projection in Afro-American folk-classical music, illustrating that a composer can create sound naturally and manipulate it, applying it towards an indication and reflection of a concept of sound that is not artificial and that can still offer some definition of our humanity.” Sound Awareness has had multiple reissues over the years.

In 1986, Brother Ah moved to D.C. and began his life as a community activist and radio personality here, all while continuing to work as an artist and educator.

While in the District, Brother Ah’s work was notably community-oriented. He taught adults at the Smithsonian and later at the University of the District of Columbia. He taught children at a Montessori School in Silver Spring, at the Levine School of Music and at classes offered through the D.C. Summer Youth Employment Program, as well as a constant roster of private students on a range of instruments and musical traditions. “His classroom was bursting with energy, and cosmic sounds,” recalled vocalist Nyame-Kye Kondo, who credits Ah’s recognition of her talent as a crucial step in her self-discovery as an artist.

He also kept busy as an in-demand gigging musician, working weddings, funerals, parties — anything the people wanted — usually for free, so long as it was his music. As he told Open Sky Jazz, “They would call me because they liked my music, so my ensemble would always be available.”

Brother Ah had been instrumental in first getting WPFW on the air in 1977, when he would travel to the District from Brown University for weekly meetings at the home of Dr. Acklyn Lynch. Initially an ardent supporter of D.C.’s “jazz and justice” radio station, Brother Ah went on to serve as the beloved host of his weekly show, “The Jazz Collectors” (later renamed simply “The Collectors”), for over 20 years. Held on Mondays, “The Collectors” was a three-hour exploration of Brother Ah’s philosophy by way of artist interviews, meditations and, of course, music.

Brother Ah’s impact on the D.C. community was widely felt. Most everyone knew him or at least knew of him — whether as a musician or as a community leader. His esteem was so widespread that, after an electrical fire set his home on Kennedy Street NW ablaze, firefighters tasked with responding to the incident rushed in to save every single instrument inside of the home, rather than dousing the building with water and permanently damaging its contents. Afterwards, neighbors, including Nasar Abadey, organized to provide not only temporary shelter for Brother Ah and his family, but also clothing, food and recovery funds.

“His records came in with all their warts and blemishes, their hisses and pops,” Stanley said. It’s hard to imagine that Brother Ah saw anything but richness and virtue in such imperfections.

For the man who will be remembered as Brother Ah, there was one continuing lesson for all of his students: that the search for truth and beauty in sound is everywhere and everlasting.![]()

Luke Stewart contributed reporting.

bob northern, brother ah, french horn, horn, obituary, robert northern, Sun Ra