Deep Groove: ‘Andrew Nathaniel White III’

“A lot of our oral history has been lost, because our educational system has failed us.”

Saxophonist and sagacious jazz educator Archie Shepp made this observation on the jazz-rap odyssey Ocean Bridges, released in collaboration with Virginia-based emcee Raw Poetic (his nephew) and D.C.-based producer Damu the Fudgemunk. Shepp’s remarks, recorded in winter 2019 and released commercially in May 2020, would prove even more insightful upon release, as the D.C. jazz scene found itself struggling to maintain those highly interpersonal oral histories amidst the virtual reality of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Shepp’s remarks raise other questions: where do we locate D.C. jazz history? Where can it be found? How can it be passed on to future generations — how can approaches to performance and composition reflective of this singular region be taught and learned?

Sadly, as the height of the pandemic would show, that cultural memory was no longer living in our clubs — the buildings that house the musicians and music. While the shells and addresses of spots like Twins, Café Nema, Sotto, Bohemian Caverns, One Step Down, Union Arts, Utopia, Marvin, Eighteenth Street Lounge and Columbia Station may live on in memory and online, the essence of those places – where jazz musicians would, as Ralph Ellison said, “observe or participate and be influenced and listen to their own discoveries transformed” — cannot be truly passed on.

But what can be passed on is a recorded history, specifically through the hundreds (at a low estimate) of recordings of music made over the decades of D.C. jazz that demonstrate our city’s unique techniques, thoughts, philosophies and musical lineage.

That is the goal of this new CapitalBop column, Deep Groove: to dig into the history of albums made by D.C. jazz musicians — or records otherwise significant in the history of the city’s scene — focusing on those “forgotten gems” and other dusty artifacts that we as an editorial organization feel are worth re-injecting into the conversation and re-introducing to our cultural memory.

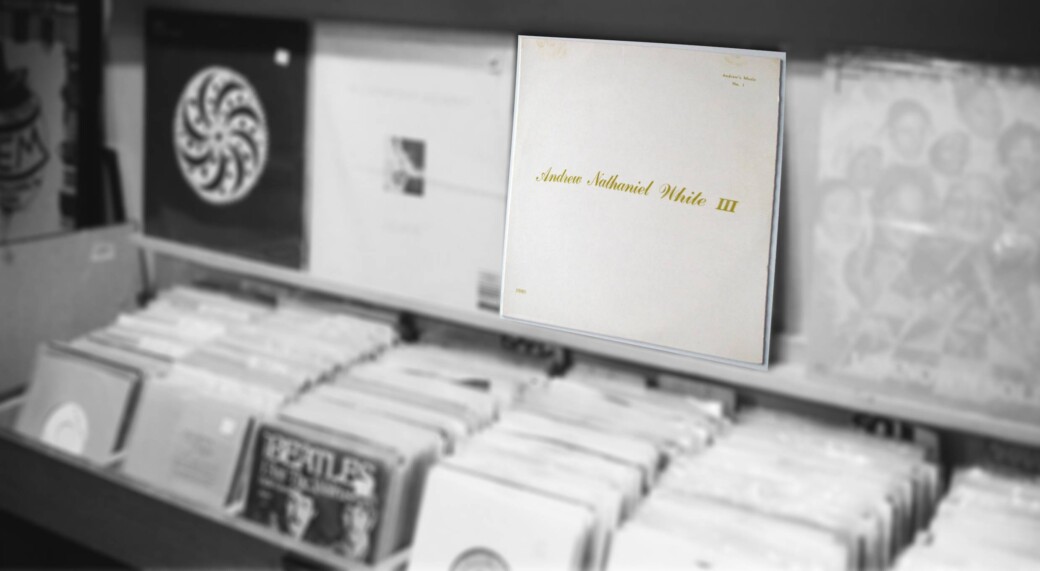

The first record in this series embodies that motive. Though found only in the dusty bins of local record stores, it contains a vital thread of the overall tapestry of D.C.’s aural history.

Andrew Nathaniel White III, the debut album by D.C. saxophonist, multi-instrumentalist, and entrepreneur Andrew White may be the ideal entry into his towering output. When the LP came out in 1973, White was already known to D.C. audiences, first a member of Howard University’s marching band, then as a member of the celebrated “JFK” Quintet — which was something of Bohemian Caverns’ house band in the early 1960s — as well as a bassist for Stevie Wonder, The 5th Dimension and Weather Report. White also spent part of the ‘60s at the Paris Conservatory of Music studying oboe, serving as principal oboist with the American Ballet Theatre from January 1968 through August 1970.

Andrew Nathaniel White III represents all of that background coming together: over 80 percent solo saxophone, oboe and English horn performing a mix of original tunes, Wayne Shorter and classical pieces.

The selection of White’s own compositions alongside baroque and romantic classical compositions and one Wayne Shorter tune gets at the heart of White’s vision for the kind of independent artist he would want to be for the next 47 years.

“My whole career started out… with a severe handicap, which is, I was told very early on that I had no commercial viability,” he told JazzTimes in 2019. “My saxophone sound has too much resonance in it, and I was told it would not register well on recording tape, so I couldn’t make good records — and they wouldn’t even know what to do with the records anyway. So, I’ve been off in the corner ever since. But nobody ever said I couldn’t play.”

Indeed, it is hard to imagine even the most adventurous Progressive Black Music label releasing this sort of album, so White had to do it himself, forming a label which he called Andrew’s Music. Andrew Nathaniel White III was its first release, and the label would go on to publish a staggering 42 LPs of White’s music over his lifetime.

The album begins and ends with different versions of “Theme,” an Andrew White original that would be something of a calling card, appearing on nearly every release in his catalog. Like the Art Ensemble of Chicago/Roscoe Mitchell’s “Odwalla (The Theme),” White’s “Theme” would become a vehicle for constant reinvention and experimentation. Performed at the album’s outset on solo tenor saxophone, White’s first offering of his “Theme” is presented contemplatively. White takes his time during breaths and rests before introducing the next melodic phrase, giving weight – though not necessarily a heaviness – to each phrase. It’s as if White knows the importance of this first introduction to listeners, and wants to get that aural handshake just right.

His next piece is an arrangement of Wayne Shorter’s “E.S.P.,” made famous by Miles Davis’ Second Great Quintet. White’s recitation of the head melody is less jagged than the version played by Shorter and Davis. It’s more rounded and mellow and breathy, more in the spirit of Coltrane during Davis’s First Great Quintet era. White then takes off on a solo that winds and twists snake-like through scales and modes, slightly mesmeric. About halfway through he takes off on sheets-of-sound solo that reaches into the kind of shrieking technique being pioneered at the same time by David Murray and Oliver Lake, weaving his initial tenor sax track with a secondary tenor track and a new alto saxophone track, all recorded by White and overdubbed in post-production. The horn lines cascade like a waterfall.

The sound of that snake-like melody comes around again on his arrangement of Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Sinfonia from the Easter Oratorio” for oboe. Introduced by an engineer saying they needed to fill three minutes of the LP, White suggests, “How about a little Bach?” Who else would put Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter and Bach next to each other on one record, particularly in 1973?

The final piece on Andrew Nathaniel White III’s side one is a bluesy double-tracked alto saxophone number, “Sacred Blues.” White blows a reedy tune that touches the kind of R&B gospel of Cannonball Adderly’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy,” before ending with a proclamation of “Yeah, baby.”

White goes from bridging the sacred and secular at the close of side one to pairing classical to modern at the outset of side two. It’s a short piece, almost more a brief tone poem, but side two opens with the first of two solo English horn pieces on this album: “Chanson de Jocelyne.” Dedicated to the woman who would be his wife of many years, and a frequent muse in his recorded output, the Chanson is a short, sweet and tender piece. There may even be a little piece of White’s signature humor that he recorded a song stylized in French on the English horn.

What follows is a series of snapshots from what White calls “Andy’s Song Book:” a rapid fire run through six White originals that are five to 10-plus years old (if we understand the years written next to them on the album’s back cover as noting when they were composed). Ranging from “Eugly’s Tune” (1961) to “Pips and Pops” (1968) and 1964’s “Andy’s Alto Sax,” each is a work of experimentation in the miniature. The last of these is a bouncy piece that sees White explore the range on his alto sax, taking melodic lines that run quickly upwards until the horn nearly pops with the sound he’s pushing out. Others, like “Eugly’s,” come off similar to “Chanson de Jocelyne” as short tone poems that melodically capture people in his life like “Cathy” and “Delores.”

White then performs the English horn solo from Tchaikovsky’s “Third Suite for Orchestra in G major, Op. 55” with his own arrangement — again underlying the centuries of musical history he grounded his sound in.

The album closes with a second version of “Theme.” Here, White performs the melody on alto saxophone, and this time pairs it with electric bass and piano tracks. Where the opening solo tenor rendition was contemplative, this version strolls along like it’s the main character’s theme in some classic noir film. The melody flows from the alto, a well-suited choice to contrast with the lower frequencies created by the bass and piano. While still a recitation of melody with no soloing, here there is instead a signal of what is to come. While no other version of “Theme” sounds like this, it sets up White for the kind of contemporary jazz combo work he will pursue on future releases. And like the end of any good noir serial, the slow fade out sees our hero walk off into the shadows — surely to return, but in what form? Who’s to say?

You can look for used copies of Andrew Nathaniel White III at your local D.C.-area record store or on Discogs.

—

This is the first article in a recurring series, Deep Groove, in which writers take a close listen to rare and out-of-print albums from D.C. jazz history.