Eliot Seppa Trio

Sotto

Wednesday, July 11, 2018

In the late 1950s, tiring of bebop’s complex harmonic language, some musicians sought to untether themselves from convention. They were seeking new ways to champion melody, and new kinds of freedom. What possibilities were available to a Miles Davis or John Coltrane if they virtually got rid of chord changes, or to a Sonny Rollins if he did away altogether with chordal instruments like pianos, guitars and vibraphones?

The languages of bebop and hard-bop still live on strongly, especially in D.C., so the questions that followed them around 50 years ago can sometimes still feel relevant today. That was the case at the Eliot Seppa Trio’s performance at Sotto on a recent Wednesday night. Seppa, a young bassist with a sturdy tone and a strong sense of swing, has established himself over the last few years as one of the most reliable sidemen on the D.C. jazz scene. When he does occasionally lead his own groups, he usually sticks to four- and five-person combos. But at Sotto, he worked with a “chordless” trio, joined only by the drummer Dante’ Pope and the bass clarinetist Todd Marcus. In that basement club — both a refuge from the bustling, happy-hour high life of 14th Street and a part of it — Seppa pushed himself to explore new possibilities, to see what could be built with melody alone.

He had a worthy team. Marcus is perhaps today’s leading practitioner on the idiosyncratic bass clarinet, and Pope is a gospel-imbued drummer whose light touch allows him the versatility of a DJ behind the kit. The trio performed a range of Seppa originals, standards and tunes culled from the deeper appendices of the American songbook.

At just 27, Seppa is still relatively new to bandleading. So far his signature touch seems to lie in his selection of material: At Sotto he brought to light some of jazz’s dustier gems from the 1950s and ’60s, and presented some original compositions that reflected his scholarly devotion to this chapter in jazz history. Early in its first set, the trio moved from the bouncing, morning-stroll bop of Wayne Shorter’s “Marie Antoinette” to the funereal dirge-turned-communal celebration of Ron Carter’s “Third Plane,” then ended the sequence with a blisteringly fast take on Sonny Rollins’ “Oleo.” Seppa’s own compositions continued the conversation: On “Sentient Being” Seppa and Pope held down an easy-swaying but tightly grooving bossa nova beat, propelling Marcus’ tonal journey — the bass clarinetist dipping into flamenco flourishes and Middle Eastern modes — and carrying a vague redolence of early Sun Ra. On the ballad “How Could You?” the trio distilled the sound of a thousand young heartbreaks into a poignant — if sentimental — tonic.

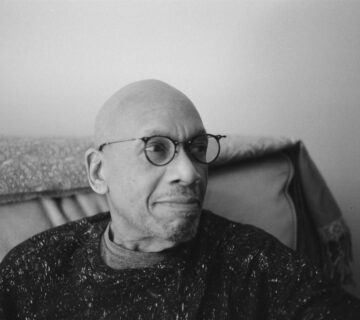

Illustration by Jake Reeves for CapitalBop

The sparse trio occasionally struggled to fill the wide-open space before them without coming apart, as Marcus’s John Coltrane-indebted “sheets of sound” flights sometimes seemed to leave the rhythm section stranded, and the occasional lack of space for Pope (playing with Marcus for the first time at this gig) left him seemingly unable to engage fully with the other musicians onstage. But you can chalk this up to a new group in its first conversations together — an exciting moment, as well as a challenging one.

But at many points, Seppa led the trio into a happy consensus. One of those moments came late in the first set, in an arrangement of Thurman Green’s “Dance of the Night Creatures” that somehow achieved a mysterious lushness. In both his accompaniments and his solo, Seppa barred notes across the fingerboard to create the illusion of a larger ensemble. Pope’s bright fills, focusing on snare and cymbals, acted as an ideal balance to the low tones of bass clarinet and double bass; Marcus’s warbly intonation filled the remainder of the soundscape just right, allowing the three instruments to create the kind of varied colors that you’d expect from a much bigger group. Elsewhere, the sheer contrast between each instrumental voice provided such a rich smorgasbord of sound that the performance was elevated through difference.

The closing number of the trio’s second set was a version of “Without a Song” inspired by Sonny Rollins’s iconic arrangement from his album The Bridge. Even with Jim Hall’s guitar in the mix, Rollins’s quartet on that album was a “chordless” group: Hall did not play harmonies, but instead operated as another horn-like voice, weaving around Rollins’s saxophone while subtly suggesting just enough harmony to fill out the acoustic expanse. At some of his trio’s finest moments, Seppa worked as more than a ballast beneath Marcus — he was another melodist, with a deep tone and an unfolding series of lyrical inventions. Should he continue to explore the trio format, Seppa has the potential to spread out even more, exploring greater freedoms, engaging in even more dialogue. ![]()

Join the Conversation →