Nasar Abadey, among the most respected drummers and bandleaders in Washington, D.C., first fell in love with his instrument as a young boy marching through the streets of Pittsburgh with his grandfather. Big, open bass drums resounded around him as he strode in the middle of a Shriners march, drummers in front of him and drummers behind.

“I felt that vibration in my chest, the ripple of sound, and I’ve been a fool for drums ever since,” he said.

Abadey speaks modestly, but the list of his accomplishments in the years since runs long. He’s a professor of jazz percussion at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore, a recipient of an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a former musical ambassador with the American Music Abroad program, administered by the State department and Lincoln Center.

These days, Abadey, 67, leads a powerful quintet, Supernova – which has a two-night run at Bohemian Caverns this weekend – and alongside pianist Allyn Johnson he directs the Washington Renaissance Orchestra, a big band that includes heavy hitters like Brian Settles, Fred Foss, Antonio Parker, Reginald Cyntje and Tom Williams, among others.

But what makes him most compelling is the way he connects a deep sense of spirituality to all his endeavors. From his loving, longstanding marriage to wife Baiyina and the genuine friendship and close bond he shares with their son Kush, to his transcendent compositions, Abadey always keeps the metaphysical close in mind.

His combo Supernova frequently graces D.C. stages in spaces like the Kennedy Center and Blues Alley, bringing a high level of improvisation and spiritual communication to loyal audiences. With his drumming and his compositions, Abadey shoots for the outer corners of the atmosphere, always searching for a higher dimension less travelled.

“I try to think in terms of, ‘What is it that I want to do that’s unique unto me, not to anyone else?’ Something that I haven’t done before that will drive me and cause me to go into areas that otherwise I would not go,” he said.

Bassist James King, a longtime friend and collaborator, said Abadey has a distinct sound—something every jazz musician must strive for, but not everyone attains.

“He has some Abadey-isms in his language. You can listen and say, ‘Oh that’s Abadey playing the drums.’ He’s got his own sound,” King said. He believes Abadey belongs in the lineup of great modern drummers and creative musicians: folks like Tony Williams, Jack DeJohnette and Max Roach.

***

Abadey has a tremendous agility on the instrument; he uses each piece of the drum set as a vehicle to lift both himself and the audience. He can shift the energy in the room with ease, and tell a story that pulls the listener in.

For him, there is a great deal of emphasis on art’s ability to heal. His latest album, Diamond in the Rough, from 2010, has a composition entitled “Eternal Surrender.” It’s an ethereal ballad written after the loss of his father that invokes an intense feeling of love and acceptance.

Abadey says the song resonates in the heart chakra, and he’s seen it move some people to tears. “That’s something we should do as performing artists: to help the audience understand the access that our art gives them to their own areas where they want to bring in light, to understand and to feel,” he said.

Kush, one of Abadey’s four children, is now an in-demand drummer and composer residing in New York. He and Nasar are often seen alongside his mother Baiyina, who is a dedicated business partner and collaborator to both. The bond between the three of them strikes a chord; they are a vision of a powerful, creative, Black family that has stood the test of time.

Kush said that in his father, he has a lifelong mentor and best friend. He’s learned to think with an open mind, to accept situations and people as they are, and to acknowledge that when things don’t manifest as expected it’s up to you to adapt, he said. Musically, Kush and his father are birds of a feather.

“I grew up listening and watching him so much that no matter how many other people influenced me, either in person or through videos, I always reference them through his sound. He can hear both of us through my playing. It’s remarkable,” Kush said.

***

Abadey’s air of balance, inner peace and deep understanding informs his music and infuses his relationships; it’s part of why he looks 10 years younger than he is. But this mindset was a long time coming.

As a high school student growing up in Buffalo, N.Y., Abadey played drums professionally in a club four nights a week, from 10 p.m. to 3 a.m., then got up for school each morning. He was playing behind everyone from vocal groups like the O’Jays and the Manhattans to shake dancers and comedians.

The club scene of the late 1960s and early ’70s was a whirlwind of nefarious elements, and it was all too easy to get caught up in drugs, alcohol and hustlers, Abadey said.

His wakeup call came at age 24, when he woke up with the right side of his face paralyzed. He visited four doctors looking for a cure for Bell’s palsy. The fourth doctor told him pure water, vitamin B and a meatless diet was his only hope, he said.

Abadey hasn’t eaten red meat in 41 years. He changed his lifestyle, eliminating meat, sugar and caffeine. Drugs and alcohol haven’t been part of Abadey’s life for decades, but he values the perspective his former experiences gave him.

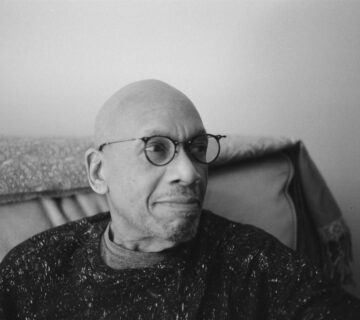

Nasar Abadey. Courtesy nasarabadey.com

“I knew that the music was always the most important thing,” he said. “I took away from all of my experiences that those were parts of life that I had to leave behind. But I had to experience it so I knew not to let it consume me. And to also explain it to my children: They’re going to get into it, so I had to help them understand how to work their way through it.”

Kush talked about Abadey’s discipline and dedication to both his health and his art. “He’s very disciplined in everything. Down to his eating habits, sleep habits and his practice schedule.”

He and Baiyina wake up and meditate in the morning before starting their days, grounding themselves in their individual spirituality and shared connection.

Their relationship is both personal and professional, and has been that way for the better part of 40 years. Baiyina handles management, booking, publicity and event production for Abadey and other artists in the D.C. area. She comes from a family of musicians: Her father was a drummer, and her mother was a vocalist who performed throughout the Mid-Atlantic cities.

Abadey said his marriage was like the Sankofa symbol, a spiral. “It’s almost like it’s full circle—that it’s all a part of the union that we have with each other: the business, the collaboration, the producing and raising of children,” he said. “So this whole thing is kind of easy for us.”

***

Abadey’s commitment to building community has been a central focus in his career. He speaks of “bringing music to people who didn’t have access.” In the late 1970s, he used an award from the NEA to produce concerts in prisons , and took his group to Brown University for a lecture and concert series.

In Buffalo, he formed Birthright, a combo with saxophonists Joe Ford and Paul Gresham, pianist Tommy Schuman and guitarist Greg Millar – both of the fusion group Spyro Gyra – and bassist Gerry Eastman. The band handled all recording, production and distribution on their own; their limited releases have become collector’s items in Japan and Europe.

During the ’80s and ’90s, Abadey was back and forth between D.C. and New York, and he toured and recorded with trumpeters Malachi Thompson and Jimmy Owens, and saxophonist Carter Jefferson.

After the birth of Kush, he focused his energy on composition, creating music that would lead to Supernova’s first official release in 2000.

Abadey’s spiritual outlook and uplifting personality define his art as they define his familial bond. As a leader in D.C.’s jazz scene, his energy has extended to other musicians and leaders in the area. He exerts a major influence upon the scene’s elasticity; unlike in other cities, musicians here largely appear to be looking for something deeper to connect with.

“I’m always searching,” he said. “Sometimes it’s a slow search, and I’m wondering, ‘When is a new thing going to happen?’ Sometimes I look up and it’s there.” ![]()

[…] to be looking for something deeper to connect with,” wrote Ms. Harris. Read the full article here. Watch a performance by Supernova here on Voice of […]