As Samora Pinderhuges gazed up from his piano, he let the final cadence of Billy Strayhorn’s signature arrangement of the jazz standard “Flamingo” reverberate throughout the Kennedy Center’s cathedral-like Grand Atrium. Taking in the packed crowd that had showed up for his ensemble’s free, mid-October performance at Millennium Stage, he addressed the audience with a forceful statement. “I want to thank the East River Jazz festival for putting on this celebration of Billy Strayhorn. Someone had to do it because his music is so underrated, in a criminal way.” Pinderhuges is not the only one who feels this way about Strayhorn, one of the jazz world’s most oft-forgotten masters.

That’s why East River Jazz chose to dedicate its entire 2015 season to the celebration of Billy Strayhorn, the composer and arranger who spent his entire career as Duke Ellington’s right-hand man and, some would say, his equal. The Samora Pinderhuges Ensemble’s performance, entitled “The Sutherland Hotel Period,” celebrated the works Strayhorn composed for the Ellington band in 1941, amidst ASCAP’s legendary radio boycott. The East River Jazz season has run for the past few months, and will culminate on Nov. 29, the 100th anniversary of Strayhorn’s birth, with a performance by Nasar Abadey’s sextet at Anacostia’s We Act Radio.

Since 2011, East River Jazz has been dedicated to promoting the music in D.C.’s often-neglected neighborhoods east of the river, as well as the occasional venue throughout the rest of the city. Washington is filled with music venues and rich music programming in many neighborhoods and quadrants, but Ward 8 possesses scant access to live music beyond what is raised up by Gray and East River Jazz. So while the organization is crucially important to celebrating Strayhorn’s life and legacy at his centennial, it also provides a creative stimulus to an overlooked area.

This year’s programming ranges from performances and jams to film screenings and literary readings; all are in some way focused on the life, legacy and surprisingly unsung catalog of Mr. William Thomas “Sweet Pea” Strayhorn. But make no mistake: These shows are not meant to be a nostalgia trip (as can be the case in some reportorial jazz programs). While the performers are dedicated to paying homage to Strayhorn’s catalog, they revive the music in a modern, more multi-faceted context.

***

The groundwork was laid two years ago, when Vernard Gray began refining his series through more thematically linked offerings. “The primary thing was that I was tired of artists having another gig and playing standards; just kind of like they were puppets,” Gray says. “A couple of years ago I started presenting programs thematically.”

Last year, Gray was looking ahead at his calendar, trying to divine what the focus of 2015’s lineup should be. “So I look at whose birthdays are coming up—significant birthdays, centennial birthdays. And here was Billy Strayhorn, Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday,” he remembers. “I’ll do Billy Strayhorn!” But Gray did not select Strayhorn out of the blue. One of East River Jazz’s most successful presentations occurred in 2013, in collaboration with the Smithsonian’s Jazz Appreciation Month, where Gray organized a series of performances celebrating DC’s own Duke Ellington.

Like many in the history of jazz, Gray would come to Strayhorn through Ellington. “Within that series, there was an ensemble led by a bassist named Herman Burney who, for his Ellington piece, presented Billy Strayhorn…It was well researched and gave you another look-see at Billy Strayhorn as a composer. I knew about Billy Strayhorn but I didn’t know all the great things he did.”

It is sadly unsurprising that even a veteran of the jazz world like Gray felt so under-exposed to the great works of Strayhorn. Over his 51 years of life, Strayhorn built a résumé as a composer, arranger, and intellectual that should be the envy of the jazz world. Born on Nov. 29, 1915, Strayhorn showed prodigious musical ability long before joining the Ellington organization. In high school, he composed the musical Fantastic Rhythm, writing the entire score, libretto, and book. During this time he also wrote some of his best known songs, including “My Little Brown Book,” “Something to Live For,” and “Lush Life.”

Upon joining the Ellington band in 1941, his first major assignment was to author a new body of numbers; he promptly produced the Ellington staples “Chelsea Bridge,” “Johnny, Come Lately,” and, of course, “Take the ‘A’ Train,” among many others, for the orchestra. From that time, until his death in 1967, Strayhorn would become Ellington’s partner in crafting the now ubiquitous sound of Ellingtonia. Through which, Strayhorn would change the face of big band and orchestral jazz. Not only did he rewrite the book on arrangements for vocal numbers—crafting accompaniment that was equal, not subservient, to the vocal melodies, which displayed unprecedented dynamics and sophistication for swing—but expanded the harmonic limitations of jazz in a way that no other composer had.

“He expanded the palette of what was acceptable in harmonies and dissonances in jazz,” says Dr. Anna Celenza, professor of music at Georgetown University, who has published several works on jazz in the era of Ellington and Strayhorn. “And that comes from studying 19th century and early 20th century French compositions, from classical music, and avant-garde music of Vienna.” Strayhorn, according to Celenza, also followed and absorbed the music from the conventional and avant-garde theater worlds of Paris and New York, allowing him to develop a wider range of influences than “that of anyone else’s in jazz at the time—and you can hear it in the orchestrations he did with Ellington.”

Strayhorn’s complex harmonies predated the angular, inverted chords that Charlie Parker and Monk pioneered in bebop, and brought the same kind of delicate yet rich sound as Debussy. Strayhorn’s music always yearned for more than most of the era’s dance-hall swing fare. It reflected his worldly and intellectual aspirations, which had consumed his every moment as a young man in Pittsburgh, and it reflected how, even as he lived in cosmopolitan centers, his heart and ears sought something more refined. Strayhorn presented stories of deeply complex human emotions—regret, world weariness, tenderness, partnership, and pure joy—expressed through mellifluous, songbird melodies and harmonics that had the sophistication of Mozart or Stravinsky.

***

While jazz musicians and scholars now have a much stronger understanding of Billy Strayhorn’s crucial contributions to the Ellington orchestra, and the music world more broadly, this is only due to developments within the last 20 years. For decades, the true breadth of Strayhorn’s work was unknown to all but a few in the Ellington organization. Academics and writers like Celenza and David Hajdu, Strayhorn’s biographer, argue that Strayhorn was inherently inclined toward privacy and voluntarily bowed out of the spotlight. Even records that included equal contributions by Ellington and Strayhorn, would rarely display both names; Strayhorn did not seem to care for the explicit credit. However, Celenza also argues that critics, fans, and scholars alike try too hard to drive a wedge between the two men. “They did really work as a team. There are some tunes that are clearly just Strayhorn’s but when I think of the Ellington sound, I actually think of the Ellington-Strayhorn sound.”

According to Smithsonian and Ellington historian John Edward Hasse, unlike Ellington, Strayhorn sought out a much wider range of musical opportunities. And in Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn, David Hajdu points out that many of these—such as the shows he wrote for the Copasetics dance group—were never covered by the mainstream, white press.

“Not many are aware that the Ellington orchestra was just one of Strayhorn’s multiple orbits,” Hasse says. “He wrote a number of pieces before ever meeting Ellington; he composed revues for a dance-and-theatrical group in New York City called the Copasetics; and he had a deep friendship with singer/actress Lena Horne, among other orbits.”

***

A key aspect of this year’s East River Jazz programming is the sheer variety, which reflects the richly diverse D.C. jazz scene, just as much as it reflects the fact that Strayhorn pulled from a variety of sources. Gray drew performers from this city’s pool of skilled straight-ahead vocalists, musicians, and ensemble groups. He also made a point of reaching out to musicians like Reginald Cyntje, Pepe González, and Nasar Abadey, whose art is connected to their ethnic heritage as well as the ethnic landscape of DC.

Gray went to all of the performers with the same question: “I’m doing this series. How would you interpret Mr. Strayhorn’s music?” Interpretation is where some of the most inventive music occurs, when one is given the freedom to build their ideas off of a master’s, instead of being shackled to the old ways. This gives a lot of freedom—a key ingredient of great jazz—to artists like Cyntje, González and, Abadey, whose own experiences in jazz and African-American music diverge from Strayhorn’s.

There is an added challenge in weaving one’s own threads into an already tightly wound fabric of music like Billy Strayhorn’s; but that is what makes the gig engaging for these artists. “It is challenging music—you can’t just pick up and play it,” says vocalist Karen Lovejoy, who will present a program titled “Strayhorn, the Giant who Lived in the Shadows,” on Nov. 27 at Millennium Stage. “His genius is so grand … it makes you examine your skill level and for a moment feel inadequate.”

Taking Lovejoy’s comments to heart, Gray is certainly accomplishing his goal of challenging performers to up their work to the next level. But there is another edge. Part of East River Jazz’s mission is furthering the contexts in which we hear Billy Strayhorn. We most frequently keep in touch with Strayhorn’s work through the channels he typically worked with: big bands, “swing” bands and arrangements for jazz vocalists. However, Strayhorn’s oeuvre has not often been translated across cultural boundaries in the same way that the works of masters like Herbie Hancock have been.

East River Jazz seeks to bring Strayhorn’s music out of the familiar American jazz and European art music formats and present it within new musical frames of reference.

Gray approached Cyntje, a favorite local trombonist, to ask if he could apply his Caribbean heritage to Strayhorn. Cyntje leaped at the chance. “The two seemed like a perfect marriage, especially on Strayhorn’s ‘Raincheck,’” he says. “I grew up in the Caribbean. As a child, I spent a lot of time listening to jazz elders combine cultural heritage with jazz standards. As a jazz musician, my Caribbean heritage comes through my music.” Cyntje presented his takes on Strayhorn—“Strayhorn, Caribbean Interpretations”—with his ensemble at the Jazz and Cultural Society in early October.

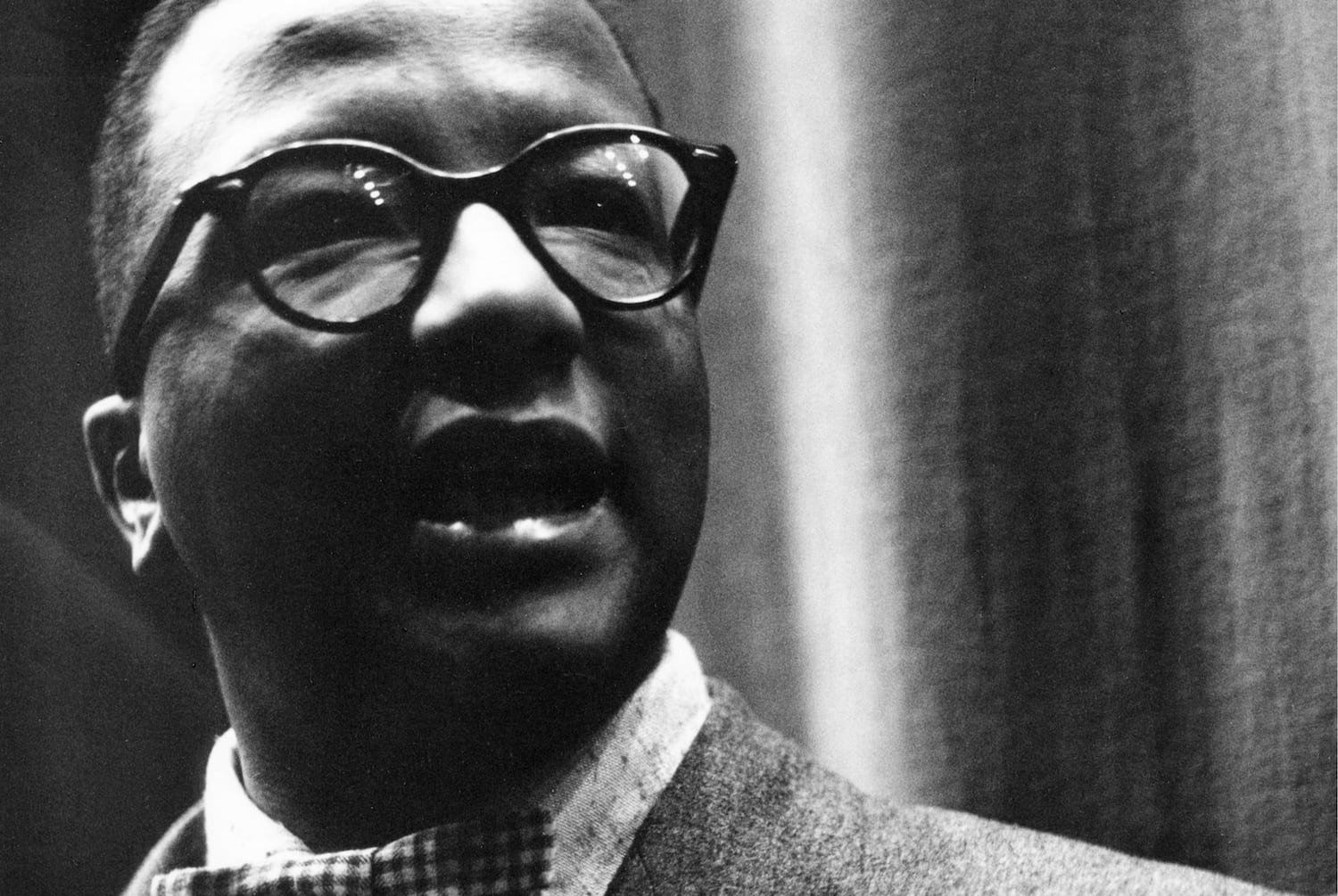

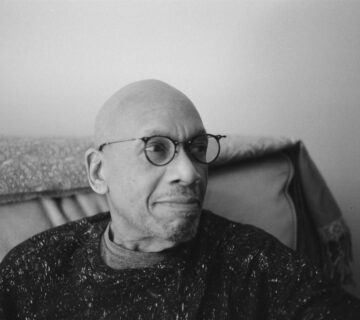

Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, c. 1960. Courtesy kuvo.org

González, a bassist, applied his Afro-Cuban heritage to Strayhorn’s catalog as well, as part of the jam performance “Strayhorn Jazz Performance, Dance & Conversation Jam” at St. Elizabeth’s RISE Center at the end of September. And Alon Nechushtan, an Israeli who lives in New York, took on the work Strayhorn created with an eastern focus in a concert with bass clarinetist Todd Marcus at the Kennedy Center.

Saxophonist Carl Grubbs will draw on saxophone players associated with Strayhorn’s compositions, when he gives a free performance at the Anacostia Community Museum on Nov. 14. Grubbs’ program will revolve around Ellington veterans like Johnny Hodges and Paul Gonsalves, but also on tertiary titans like John Coltrane, who was Grubbs’ first teacher. On the link between Strayhorn and Coltrane, Grubbs says, “As a follower of Coltrane, I checked out the tunes that he selected and often use many of these in my performances.I hope to educate the audience on the art of composition and how music is used to express one’s feelings, hopes, dreams, etc. His [Strayhorn’s] music has influenced my artistry to the extent that I too try to paint a picture of life’s experiences as I compose and perform.” As a disciple of both Strayhorn and Coltrane, highlights the links between how these two titans told stories with their music.

It is insights like these that make the heart of the East River Jazz operation, according to Gray, “What I’ve been really influenced by is that [the musicians have] taken this man’s music…and even though they’ve said it’s really difficult, they stepped up to the challenge to do their own stuff with it.”

***

Within the jazz world, recent books like David Hajdu’s Lush Life and Martin Van de Leur’s Something To Live For have helped enshrine Strayhorn in the collective consciousness. But his name is scarcely a whisper in other circles of the music world—which is a shame, since he has lessons to offer any musician or composer.

Some songwriters and composers today point to Strayhorn’s mastery of melodic composition as among his greatest lessons. “When I listen to his music I feel his musical storylines are very genuine,” says Gracie Terzian, a rising jazz vocalist and Herndon, Va. native. Though she is not an East River Jazz performer this year, Terzian cites Strayhorn as a font of inspiration for her own songwriting. “When a composer is able to write in a way that I think comes from following a real musical storyline, you can tell that it’s coming from a more special place.”

Pinderhuges points to Strayhorn’s song craft as providing sterling examples in succinctness. “He taught me about simplicity, and how much work that takes,” the pianist said. “Simplicity does not mean doing the easiest thing, it means taking as much time as needed to figure out how to get the strongest possible version of an idea, where nothing is superfluous.”

But perhaps the greatest lessons offered by Strayhorn’s music and the presentations of East River Jazz are not musical, but emotional. For Hajdu, Strayhorn’s biographer, the main lessons of his music lie at the heart of the composer himself: “Don’t fake it, don’t pretend, trust yourself, be yourself,” he says. “Do things because you want to, because you love them … because Strayhorn did everything for love.” ![]()

[…] https://www.capitalbop.com/portrait-of-a-stray-thread-east-river-jazz-celebrates-the-legend-of-billy-… […]

[…] Billy Strayhorn at 100: East River Jazz Celebrates a MasterCapitalBop: Download / Stream Take the "A" Train (1999 Remastered) by Duke Ellington & His Famous Orchestra. Full Mp3 Track / Zip Album available for Free Download. Working Links: Torrent, CDQ, Mp3, 320, Alac, iTunes. […]