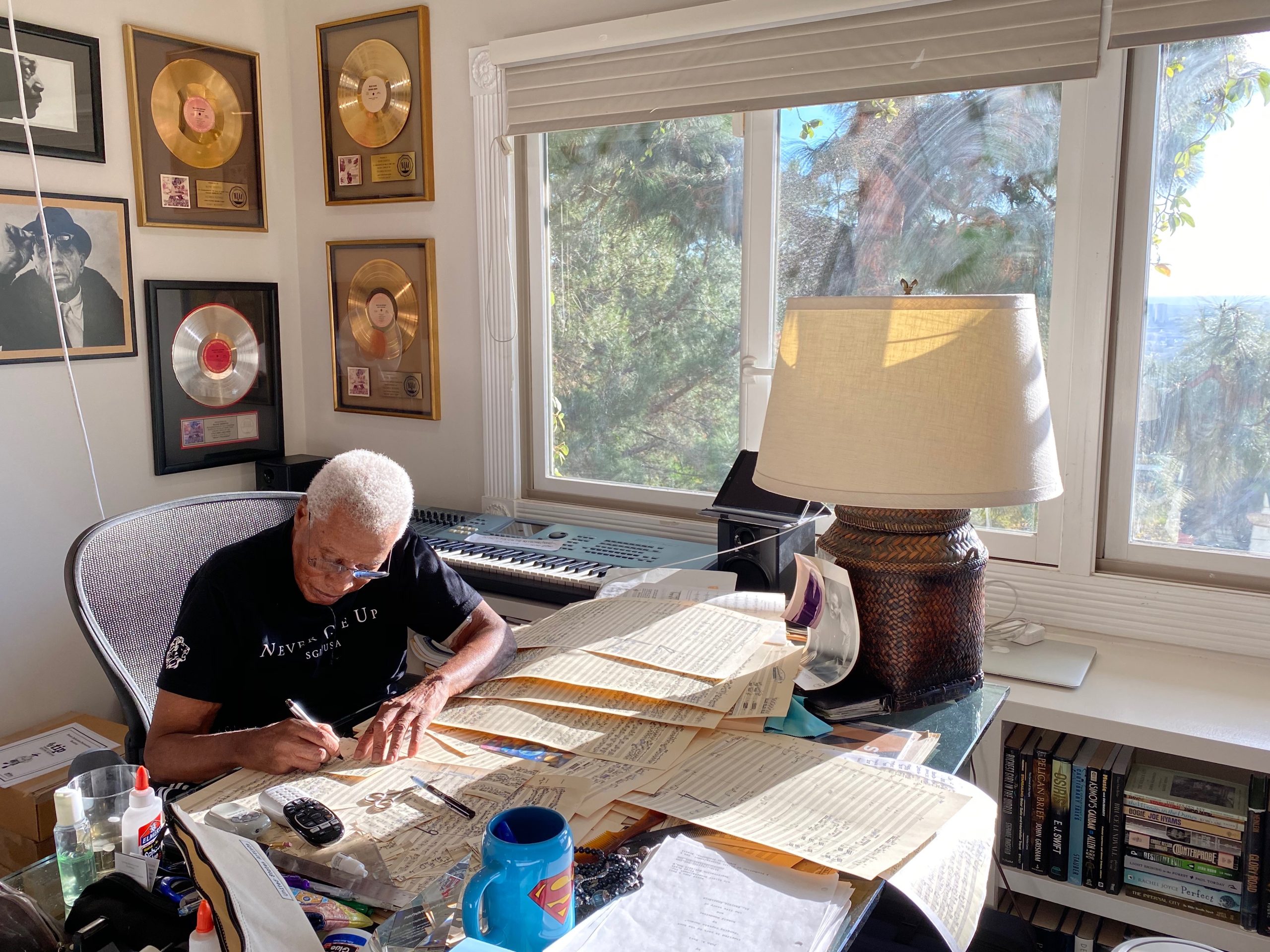

There’s a story Wayne Shorter often tells that encapsulates a lot of his artistic vision these days. “We played in a vacant lot when we were kids,” explains Shorter, 88, on a recent call from his home in Los Angeles. “We’d say, ‘Let’s go outside and play during the summertime.’ That vacant lot became the Sahara Desert, Mars, an ocean, it became all kinds of stuff. We’d play all in this vacant lot. Our parents would come home from work and ask us, ‘What have y’all been doing?’ And we’d say, ‘Nothing.’ I want to find out, even now, what that nothing was.”

Shorter’s most recent foray into rediscovering the vast, unstructured, free space of that vacant lot is Iphigenia, a new opera he created with bassist/singer/songwriter/savant Esperanza Spalding. He wrote the music, and she wrote the libretto; she is also cast as the lead. Iphigenia arrives at the Kennedy Center this weekend for its D.C. debut. (Both the shows, on Friday and Saturday, are sold out.) Shorter said he had dreamt of writing an opera since he was a student at New York University in the 1950s. And he said Iphigenia is informed by every work he’s created since, though he sees it less as a culmination and more as just another step along his continuing creative path.

The opera reworks the story of Iphigenia, the daughter of King Agamemnon, who offered her up for sacrifice to appease the goddess Artemis on the eve of battle. Spalding worked with dramaturg Sunder Ganglani to render a postmodern treatment that seeks to put Iphigenia’s perspective at the center of the opera.

To speak with Shorter is to get a peek into a mind that has transcended most typical notions of human creativity. In a nearly 90-minute conversation this week, he referenced everything from the architect Frank Gehry (who designed the set for Iphigenia) to LL Cool J to Neil DeGrasse Tyson to Dune. Below are four of the most enlightening snippets from that conversation. (The transcript has been edited and condensed.)

Why Shorter wanted to write an opera.

When people start studying what opera is about, and the first people that got into formulating what is now known as opera — as I call it, “Monteverdi and the cats” [laughs] — they used to play indoors, IN recital halls and all that. And someone said: “Let’s go outside and play.” So, they had the money behind them — the principalities and aristocracies and kings and queens — and they had a big back yard to play in. They started dancing and doing poetry and telling stories.

So, a good explanation of what opera is, is: “Opera is everything goes!” There are no rules. But people try to make rules and make things stick. They make rules about being able to enter as a part of the audience; you have to be a part of a hoity-toity, aristocratic, tuxedo-wearing set, and be able to pay the price to get in. The opera itself started to formulate the hierarchy of “conductor,” “concertmaster” and all of that. And the soloist, the arias, the recitatives, a lot of marches, the whole thing about tragedy. But I think the guys — the cats, from Puccini to Giuseppe Verdi and going back to Mozart — Mozart hung out with the regular people on the streets, didn’t he?

The hoity-toity, as I call them, have had the upper hand long enough. Now it’s time for things to be written to serve as a battering ram to this artificial, cold requirement to be a part of something called the opera.

In a 2016 interview, Shorter praised the novelist Haruki Murakami, who has written about not being sure he could write a novel until he wrote his first one, Wind/Pinball. I asked Shorter whether the same was true of him and Iphigenia.

I never thought about, “Could I write an opera?” I thought, “Was it time for it?” When I first started, it was a thing called The Singing Lesson. [Shorter’s first concept for an opera, The Singing Lesson was never fully written]. This was way back in the NYU days, at the same time that Leonard Bernstein was doing West Side Story. I just let that writing lie while I graduated, went to the Army and all. I knew that this thing would creep up. This little baby wanted to grow. The baby has been being urged by everything I have written; everything I write. To me, there’s no such thing as an ending: You just say, “You’re finished doing this,” or, “I’m not doing that anymore.” But the “this” and the “that” when you’re done, they are a conversation about something larger, something more enhancing, something more in depth. Like every cell in your body is supporting the full-grown body, the full growing body of a person.

I think everything I have worked on or written from 1959, going into Art Blakey’s band and Miles Davis’s and Weather Report and beyond to now, every piece of music I have written is like a cell that belongs to a large body.

Shorter’s thoughts on Iphigenia’s conductor, Clark Rundell.

I met him in Liverpool: He was conducting the orchestra there. When I walked in the room, I saw him and I said to myself, “Damn! He looks like Clark Kent.” But he’s more than that look. He’s not a dictator to the orchestra, to members, and all that stuff. He doesn’t stand on the desk and say “Come on! You gotta: dah-dah-dah.” He’s the total opposite. He says, “OK, let’s start this again and let’s all be brave. Let’s be brave.” So, whatever they’re afraid to do with their instruments, he says, “Just do it! Don’t be scared.”

With Miles Davis, when somebody came up on the stage to do something — a brand-new person — and Miles wanted them to come out, and they were hesitant, Miles would say: “What’s the matter? You scared?” I was thinking he was actually thinking of himself when he was young and he couldn’t play the part of “Ko-ko” with Charlie Parker, and Dizzy Gillespie had to do it. Miles couldn’t do it, he was 18, 19 something like that. But he used that as a springboard for never going backwards or being afraid.

…And on his relationship with John Coltrane.

John Coltrane invited me to his house when he heard me play with Horace Silver at a matinee. This is all leading to the opera — whether you know it or not, whether I knew it or not. We were tearing down the bandstand and this lady tapped me on the shoulder and said, “My husband wants to meet you.” I turned around and I said, “Who?” It was John Coltrane standing there. He asked me to come to his house. I went to his house and he didn’t want me to leave.

I think I spent part of a week there, they made a bed for me and all that stuff, and we would talk and play together. We would play the piano, exchange ideas and all of that. He told me — he was with Miles Davis then — he said, “I’m gonna leave Miles.” And I said, “Oh yeah?” And he said, “You can have that spot if you really want it.”

There was a Thanksgiving dinner my mother cooked and John came all the way from New York, by himself, on the train, to my mother’s Thanksgiving dinner. And we just had a good time.

Join the Conversation →